A 40-year-old man underwent a split-night polysomnogram that revealed an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 45 events per hour, with successful titration to effective CPAP of 10 cm H2O with nasal mask. He was diagnosed with severe OSA and was prescribed CPAP of 10 cm H2O. On delivery of CPAP, the durable medical equipment provider achieved a good seal with a nasal mask.

After 4 weeks of adherent CPAP use, he reports some improvement in daytime sleepiness. Pretreatment Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) score was 18/24, which decreased to 13/24 (scores >10 are consistent with clinically significant hypersomnia). He has no other comorbidities and is not taking any medications or over-the-counter substances. He sleeps approximately 8 hours each night. He has noticed increased mouth dryness since starting CPAP use.

Review of the CPAP download data shows average nightly CPAP use of 7.9 hours, percentage of nights used ≥4 hours of 100%, average residual AHI estimated by the CPAP device of 19 events per hour (consisting of apneas that are labeled as unclassifiable), and unintentional median mask leak of 35 L/minute (upper limit of normal is 24 L/minute).

Which of the following would be the most appropriate next intervention?

A. Increase CPAP to 13 cm H2O owing to high residual AHI of 19 events per hour.

B. Refer the patient to be evaluated for hypoglossal nerve stimulation.

C. Switch to BPAP.

D. Add chin strap to nasal mask.

D. Add chin strap to nasal mask.

This patient’s persistent hypersomnia is due to inadequately treated OSA from excessive mask leak.

Correct management: Add chin strap to reduce mouth leak

A 56-year-old man with subacute progressive dyspnea on exertion is diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis on the basis of compatible history, physical examination, and chest CT scans. His medical history includes seizure disorder, chronic kidney disease, peptic ulcer disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. His physician plans to start antifibrotic therapy.

Which of the following would make pirfenidone the preferred agent?

A. Concomitant use of phenytoin for seizure disorder

B. Estimated creatinine clearance of 34 mL/min (0.57 mL/s/m2)

C. Hemoglobin A1c of 7.1% (0.07 proportion of total hemoglobin)

D. Severe allergic reaction to sulfonamides

A. Concomitant use of phenytoin for seizure disorder.

Nintedanib is a substrate of P-glycoprotein and is metabolized by CYP3A4. Consequently, concomitant use of strong CYP3A4 inducers (eg, carbamazepine, phenytoin, and St. John's wort) with nintedanib should be avoided because these drugs decrease concentrations of nintedanib and may impair its effectiveness.

A 45-year-old woman is referred to you for evaluation by her gastroenterologist. She has a 5-year history of worsening ulcerative colitis, and her GI doctor would now like to start infliximab. As part of the evaluation, they ordered an interferon-γ release assay, which was positive. Her chest radiograph shows a 4-mm calcified nodule in the right upper lobe, and induced sputum for acid-fast bacilli was also ordered and was smear-negative. The patient reports no fevers, chills, and sweats; has no other significant medical history; and feels well from the pulmonary standpoint. She has no history of immigration from a high-risk country, or known TB exposure, and she works as a librarian. She is a never-smoker. Her lung examination is clear. Her chest radiograph confirms the findings as described. Routine labs reveal mild iron-deficiency anemia, normal liver function, and negative HIV and pregnancy tests. Which of the following do you recommend?

A. Begin isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide for 6 months.

B. No additional treatment is needed.

C. Begin rifampin and pyrazinamide for 2 months.

D. Begin rifampin for 4 months.

D. Begin rifampin for 4 months.

In patients about to start TNF-α inhibitors, LTBI must be treated first, with rifampin 4 months (4R) as the preferred regimen due to efficacy, safety, and higher completion rates.

A 62-year-old man with a history of adenocarcinoma of the prostate with bone metastases has been undergoing chemotherapy with good response on the basis of imaging and tumor markers, with the exception of a solitary left upper lobe pulmonary nodule that has grown from 11 to 16 mm over the past 9 months. All other clinical evaluation of tumor burden from the prostate cancer had shown a response to chemotherapy. He has a 30-pack-year history of smoking and quit 20 years ago. Other medical history is significant only for hypertension. His physical examination results are remarkable for moderate obesity, no palpable lymphadenopathy or finger clubbing, and normal lung examination results. Pulmonary function test results reveal normal spirometry and diffusing capacity.

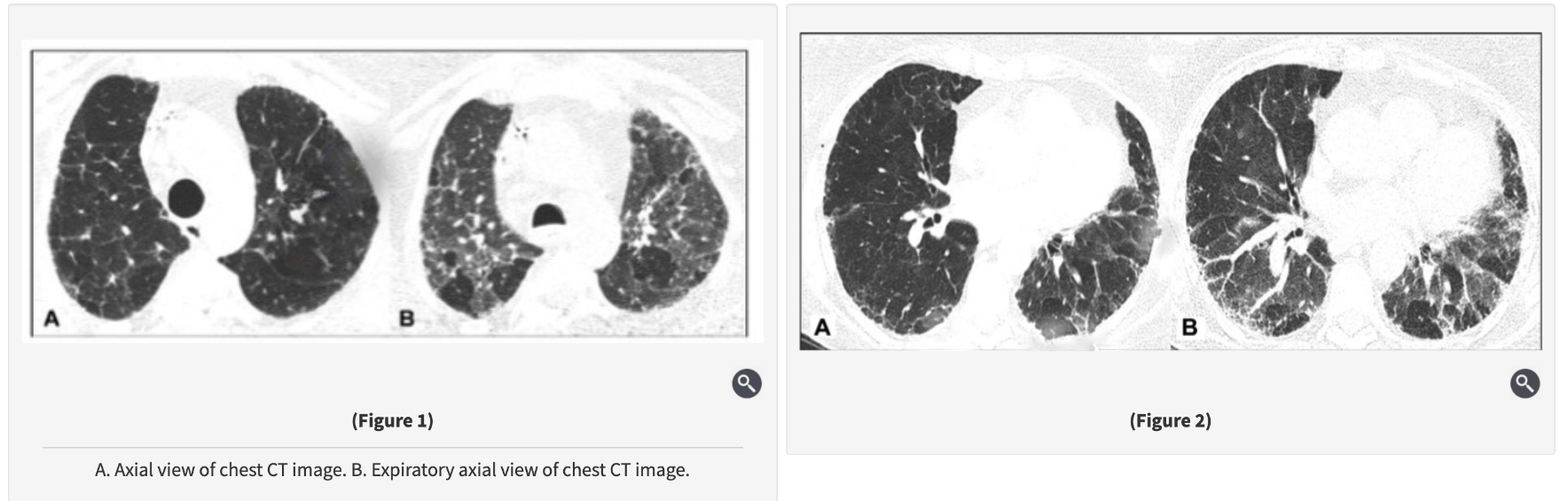

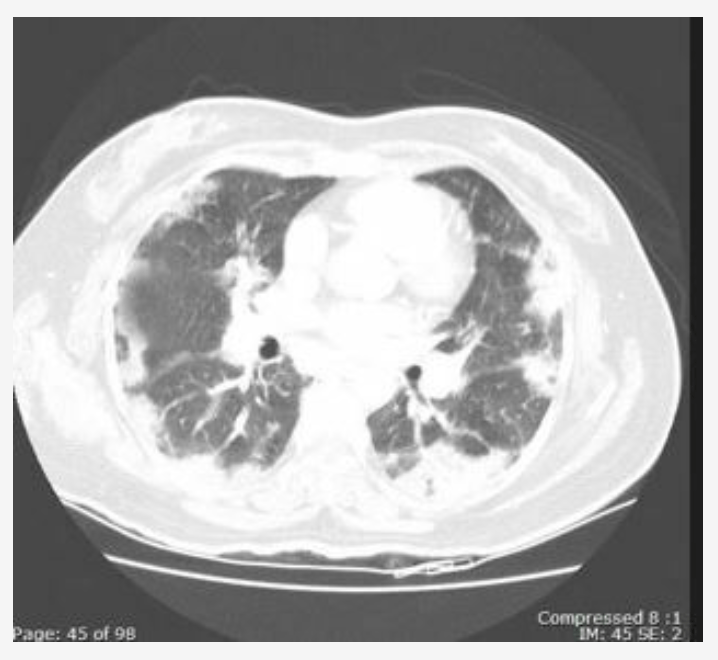

A recent PET/CT scan demonstrates a 16 × 15-mm nodule with maximum standardized uptake value of 3.2 (average liver, 2.7), with no other abnormalities beyond his known lytic bone lesions. Aside from the increased size of the nodule on the CT scan (Figure 1), there are no other concerning changes on the PET/CT scan. A recent serum prostate-specific antigen level was 1.4 ng/mL (1.4 μg/L), lower than 3 months earlier.

Which of the following is the best recommendation?

A. Continue chemotherapy with CT scanning surveillance.

B. Perform bronchoscopic tissue sampling or excisional biopsy.

C. Continue chemotherapy with PET/CT scanning surveillance.

D. Perform radiofrequency ablation or stereotactic body radiotherapy.

B. Perform bronchoscopic tissue sampling or excisional biopsy.

Patient with metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma on treatment

General improvement in systemic disease, except for 1 growing pulmonary nodule

Risk factors: age >60, heavy smoking, prior cancer, upper-lobe location, interval growth

PET SUV 3.2 → moderately suspicious

In cancer patients, don’t assume every lung nodule is a metastasis.

If a solitary, enlarging, PET-avid lesion is found—especially with risk factors—treat it like a primary pulmonary malignancy until proven otherwise.

A 74-year-old woman is referred to you for persistent hypersomnia despite adequate adherence to nasal CPAP therapy. The patient is a retired lawyer, but she is frustrated about not being able to sustain wakefulness during social gatherings with her friends and family. Her medical history is pertinent for well-controlled hypertension and hypothyroidism. She was diagnosed with severe OSA 1 year ago and was prescribed auto-CPAP therapy set at a minimum pressure of 6 cm H2O and a maximum pressure of 14 cm H2O. She reports going to bed at 11:00 PM, has a short sleep latency of 10 to 15 min, and wakes up spontaneously without any alarm at 7:30 AM. She estimates getting close to 8 h of sleep each night. An objective CPAP download reveals she is using it 100% of the nights, with a mean use of 7 h 50 min per night. There is minimal mask leak, and the residual apnea-hypopnea index estimated by the auto-CPAP device is four events per hour. The median pressure delivered is 9 cm H2O, and the maximum pressure is 12 cm H2O. She reports some improvement in daytime sleepiness after initiating auto-CPAP therapy. Her Epworth Sleepiness Scale score before initiating auto-CPAP therapy was 18 out of 24 (scores >10 are suggestive of hypersomnolence). During the current visit, her Epworth Sleepiness Scale score has decreased to 13.

Which of the following interventions is most likely to improve this patient’s residual daytime sleepiness?

A. Ask the patient to wake up at 8:30 AM instead of 7:30 AM (ie, sleep extension).

B. Increase the maximum level of the auto-CPAP device from 14 cm H2O to 18 cm H2O.

C. Increase the minimum level of the auto-CPAP device from 6 cm H2O to 9 cm H2O.

D. Prescribe modafinil.

D. Prescribe modafinil.

Residual hypersomnolence occurs in up to 15% of patients adherent to CPAP, even with good control of OSA.

Wake-promoting agents (eg, modafinil, armodafinil, solriamfetol) are appropriate if:

CPAP adherence is good.

Residual AHI is low (<10–15/h).

Mask leak is minimal.

Other causes (sleep deprivation, depression, medication effects) are excluded.

- Choice A (extend sleep by 1h):

Pt already sleeps ~8h, wakes spontaneously.

No evidence of insufficient sleep.

- Choice B (increase max pressure to 18 cm H₂O):

Device never reaches current max (14).

Raising it won’t help residual hypersomnolence.

- Choice C (increase min pressure from 6 to 9 cm H₂O):

Residual AHI = 4 → OSA is well controlled.

No need to increase pressure.

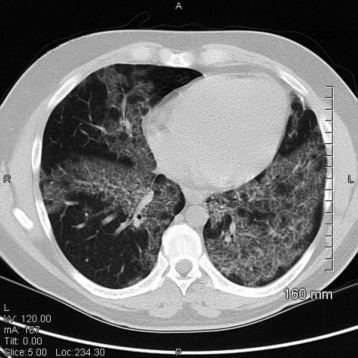

A 72-year-old man, who is a former smoker (20 pack-years) with a medical history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal disease, presents with slowly progressive shortness of breath and nonproductive cough for the past year. He is a retired car mechanic and lives with his wife in a mobile home with a history of water damage 2 years ago without any visible mold. However, professional mold testing confirmed the presence of elevated Penicillium levels in the kitchen area, but this has not yet been remediated owing to high cost. His medications include aspirin, lisinopril, atorvastatin, and omeprazole. His family history is negative for pulmonary fibrosis or autoimmune disease.

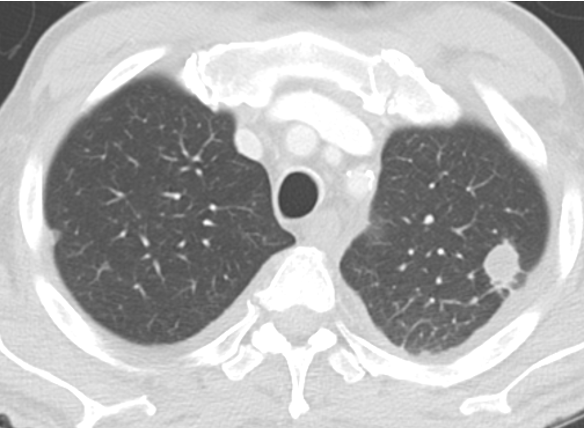

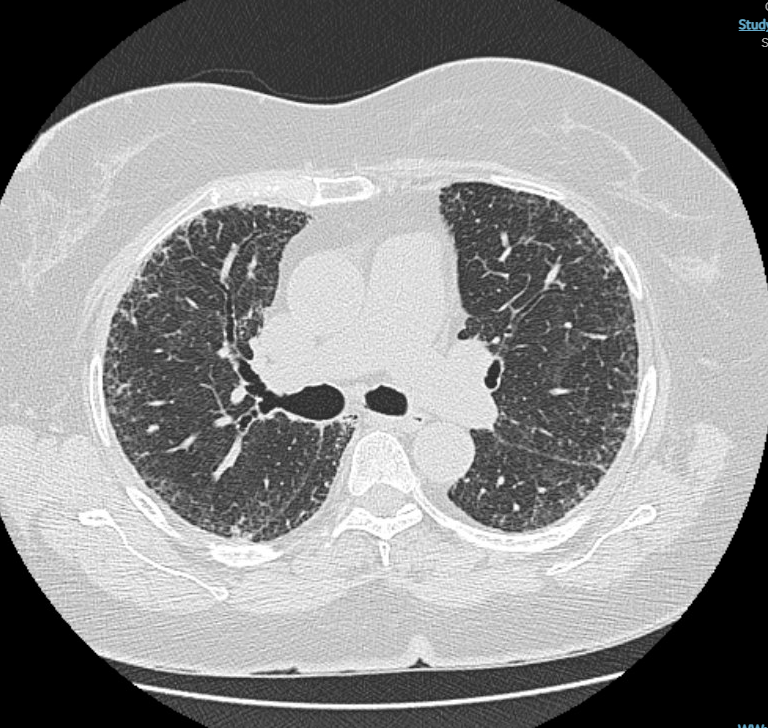

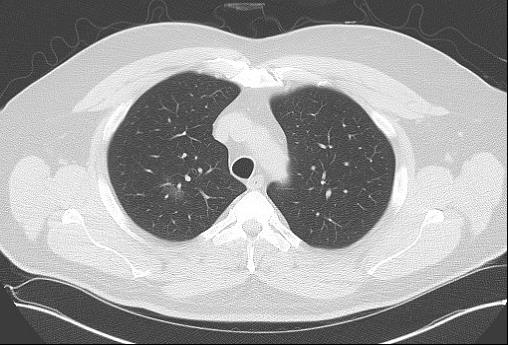

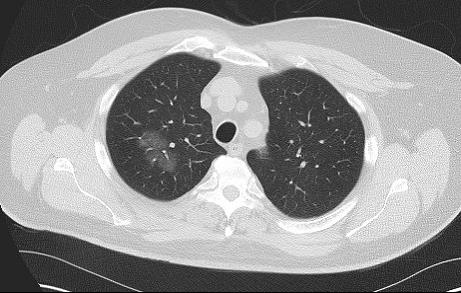

Physical examination is remarkable for bibasilar fine crackles, mild upper lobe inspiratory squeaks, and mild bilateral distal interphalangeal joint arthritis without swelling. The laboratory tests including autoimmune serologies are notable for mildly elevated antinuclear antibodies (1:160 titer, homogeneous pattern), mildly elevated rheumatoid factor, and negative findings on anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) and hypersensitivity pneumonitis serology panel. His pulmonary function testing showed FVC of 55%, total lung capacity (TLC) of 59%, and DLCO of 52% predicted. On the 6-min walk test, he walked 1,200 ft (360 m) with mild exertional desaturation on room air from 95% to 91%. Chest high-resolution CT (HRCT) images are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

A. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease

B. Nonfibrotic HP

C. Fibrotic HP

D. IPF

C. Fibrotic HP

Significant mold exposure (penicillium).

Typical HRCT findings: fibrosis + bronchiolar obstruction (centrilobular nodules, GGOs, mosaic attenuation, air trapping, three-density pattern).

Clinical features: insidious cough, exertional dyspnea, bibasilar crackles, inspiratory squeaks.

Rheumatoid arthritis–associated ILD: unlikely here → distal interphalangeal arthritis (osteoarthritis), negative anti-CCP, no family history. ❌ Choice A.

- NFHP: less likely due to presence of fibrosis and chronic course. ❌ Choice B.

- IPF (UIP pattern): lacks typical exposure link; HRCT shows UIP pattern with honeycombing, unlike this case. ❌ Choice D.

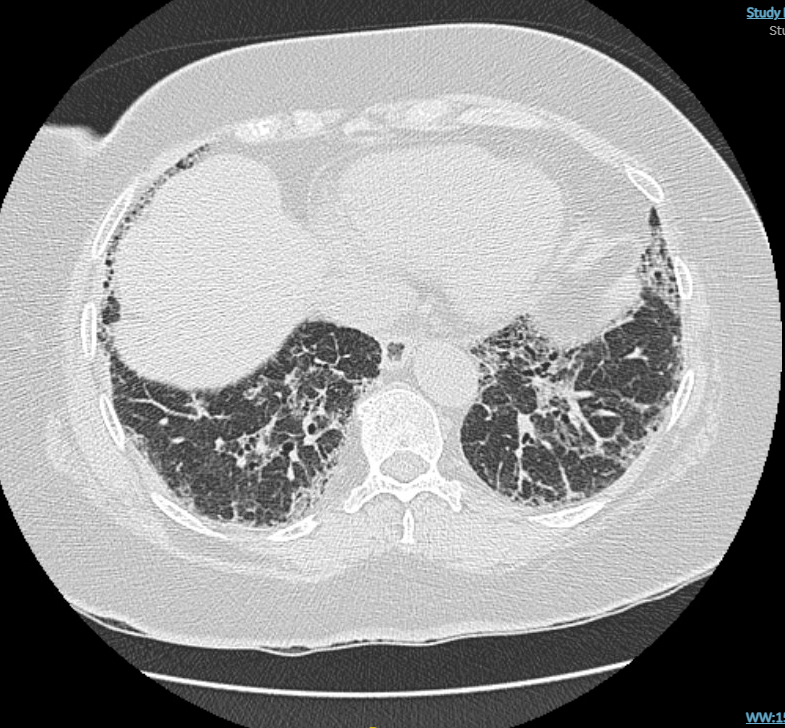

A 42-year-old patient with a history of diabetes mellitus who lives in eastern Washington state has had 4 weeks of dry cough, fatigue, and night sweats. The patient has also had joint pain in bilateral ankles, knees, and wrists and a painful rash on the shins. On examination, the patient is afebrile with a pulse of 80/min, respiratory rate of 18/min, BP of 140/85 mm Hg, and SpO2 of 96% on room air. Auscultation of the chest is notable for crackles in the left lower lung. There is no joint swelling or erythema noted. Tender, erythematous, nonulcerated nodules are present on bilateral shins. Chest radiograph (Figure 1) shows an infiltrate in the left lower lung and an upper left lung nodule, confirmed by CT scan of the chest (Figures 2 and 3). Serologic testing confirms the diagnosis.

Which is the best treatment for this patient?

A. Fluconazole

B. Voriconazole

C. Amphotericin B

D. No treatment

A. Fluconazole

Symptoms: Dry cough, arthralgias, erythema nodosum (classic triad in endemic regions).

Risk factor: Diabetes mellitus → ↑ risk for complications.

Disease severity: Moderate (symptoms >3 weeks).

In endemic areas, moderate pulmonary coccidioidomycosis with risk factors (like diabetes) should be treated with oral azoles for 6–12 weeks to prevent complications and dissemination.

Voriconazole (B) → not first-line, limited data for pulmonary coccidioidomycosis.

Amphotericin B (C) → reserved for severe or disseminated disease.

No antifungal therapy (D) → appropriate for mild disease without risk factors, but not in this patient.

An 84-year-old woman had lung cancer diagnosed—T1bN2M0 adenocarcinoma with lymphovascular invasion and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) L858R and TP53 mutations. She underwent a lingular segmentectomy and has been receiving adjuvant osimertinib for the past 9 months. Her other medical history includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypothyroidism, and osteopenia.

She notes some fatigue. Her activities are more limited by back pain (sciatica) than by her breathing. She has a mild morning cough. She does not have chest pain or fevers. Her appetite is fair. She requires loperamide for diarrhea control and has lost a bit of weight over time. She does not have new headaches or vision changes. She does not notice any gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms or swallowing difficulties. She has not had any respiratory infections requiring treatment.

On examination, she was afebrile, in no apparent distress, speaking full sentences, with an Spo2 of 96% breathing room air. Her chest was clear with regular rate and rhythm and no edema.

Chest CT scanning showed diffuse mid- to lower-zone interstitial changes, largely new, occupying 10% to 20% of the lung parenchyma. Results of a CBC count and comprehensive metabolic panel are normal. The N-terminal prohormone of brain-type natriuretic peptide level is normal. A recent echocardiogram shows normal left ventricular function. Results of a viral respiratory panel, including influenza and SARS-CoV-2, are negative.

Which of the following is the most appropriate next step?

A. Use empiric antibiotics.

B. Use systemic corticosteroids.

C. Discontinue osimertinib.

D. Monitor without change in treatment.

C. Discontinue osimertinib.

Patient on osimertinib (EGFR inhibitor) for EGFR-mutant NSCLC.

Imaging: focal/mild pneumonitis (<25% lung parenchyma).

Symptoms: minimal or absent, normal oxygenation.

Risk factors: prior smoking, prior checkpoint inhibitor therapy, concurrent radiation (general considerations).

Most likely diagnosis → Osimertinib-related pneumonitis (grade 1).

Best management → Discontinue osimertinib

Steroids (B) → not mandatory for grade 1 pneumonitis.

A 56-year-old overweight woman with no medical history is referred to you for evaluation of OSA. She complains of loud disruptive snoring, excessive daytime sleepiness, and daytime fatigue. Her spouse is unwilling to sleep with her in the same room. Physical exam reveals a BMI of 28 kg/m2. Her oropharynx is crowded. The remainder of the physical exam is normal. Recently, her primary care provider ordered a sleep study that demonstrated mild OSA, with an apnea-hypopnea index of 12 events per hour. Treatment with nasal CPAP was initiated, but the patient could not tolerate CPAP, despite multiple mask changes and CPAP device adjustments with an experienced respiratory therapist, as well as discussions with a primary care provider with educational interventions emphasizing the importance of CPAP adherence. She remains very interested in treatment but simply cannot tolerate having a mask on her face. In fact, she finds CPAP more disruptive to her sleep. What would you recommend?

A. Referral to sleep dentistry for mandibular advancement device evaluation

B. Continuing to try use CPAP

C. Referral to otolaryngology for hypoglossal nerve stimulator evaluation

D. No need to treat because mild OSA is not associated with cardiovascular disease or increased mortality

A. Referral to sleep dentistry for mandibular advancement device evaluation

These devices are first-line therapy for mild to moderate OSA and an important alternative when CPAP is not tolerated.

Randomized clinical trials: show improvements in

Daytime symptoms (eg, sleepiness, fatigue).

Quality of life.

Bed partner’s sleep and quality of life.

Cardiovascular outcomes: Mild OSA not strongly linked to increased CVD/mortality, but treatment improves patient-centered outcomes.

A 65-year-old woman with a history since childhood of mild asthma that is well controlled with an inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β-agonist and a leukotriene receptor antagonist presents with 3 to 4 months of increased shortness of breath, a mildly productive cough of white sputum, and low-grade fevers. Her medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She is receiving no additional medications. She is a never smoker and does not drink alcohol or use drugs. There is no recent travel history.

Her physical examination results are remarkable for a temperature of 38.2 °C, and she has scattered crackles and wheezes at lung examination. Her Spo2 breathing room air is 88%. Laboratory test results reveal a WBC count of 11,000/µL (11 × 109/L) with 25% eosinophils. BAL is performed, and results show 30% eosinophils. Stains and cultures are negative for infectious organisms. Blood cultures are negative, and her IgE level is 400 IU/mL. Test results for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are negative, and the urinalysis results are unremarkable. Pulmonary function test results reveal a ratio of 65% and total lung capacity of 78% predicted. Her chest imaging is shown in Figure 1.

What is the likely diagnosis?

A. Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia

B. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis

C. Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia

D. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis/mycosis

C. Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Subacute course (weeks–months).

Female predominance (3rd–5th decade).

Peripheral eosinophilia (25–30%).

BAL eosinophils ≥30–40%.

Characteristic chest imaging: bilateral, peripheral or pleural-based opacities, sometimes called the “photographic negative” of pulmonary edema.

Often associated with asthma (50–75%).

Acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP):

Acute, fulminant → respiratory failure.

BAL eosinophilia, but no peripheral eosinophilia.

Dramatic steroid response; relapse rare.

❌ Choice A.

- EGPA (Churg–Strauss):

Vasculitis with long-standing asthma, sinusitis, neuropathy.

Positive ANCA, extrapulmonary disease (skin, heart, kidney).

❌ Choice B.

- ABPA:

Severe, refractory asthma.

Imaging: central bronchiectasis, “finger-in-glove” opacities.

IgE >1000 IU/mL, positive Aspergillus-specific IgE/IgG.

❌ Choice D.

A 24-year-old patient with cystic fibrosis (CF) is seen in the clinic for routine follow-up. They report no change in pulmonary symptoms and specifically have not had any increase in cough, sputum production, chest tightness, or wheezing. The patient has mild lung disease with FEV1 of 85% predicted. During the visit, sputum culture is obtained and grows Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The patient has never had this grow on samples collected in the past.

Which of the following is the most appropriate next step in management?

A. Observe and repeat sputum culture in 1 month.

B. Initiate 28-day course of inhaled tobramycin.

C. Start oral ciprofloxacin and repeat cultures in 3 months.

D. Initiate IV ceftazidime and tobramycin.

B. Initiate 28-day course of inhaled tobramycin.

Cystic fibrosis with early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection

Early eradication is critical → prevents chronic colonization, which worsens lung function and morbidity.

Evidence

ELITE trial:

28-day course of inhaled tobramycin → effective, well tolerated.

Prevents progression to chronic colonization.

A 63-year-old woman has a 1.5-cm fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid nodule in the left lung apex, as well as FDG-avid para-aortic lymph nodes, during an evaluation of unintentional weight loss. Results of a transthoracic needle biopsy reveal an adenocarcinoma in the left upper lobe nodule (mutation and programmed cell death ligand 1 negative). Results of endobronchial ultrasound-guided bronchoscopy staging were negative. She is being considered for neoadjuvant chemoradiation to be followed by a left upper lobectomy.

She currently feels well. She can walk up to half a mile without dyspnea and is able to climb two flights of stairs. She has a chronic cough with some clear sputum production. She does not have cardiopulmonary or systemic symptoms, other than weight loss. She currently smokes one-half a pack per day of cigarettes. She has a history of COPD, with her last acute exacerbation 6 months ago. She has coronary artery disease with a myocardial infarction 2 years ago, a carotid endarterectomy after a transient ischemic attack, and treated hypertension.

Spirometric results show moderate obstruction (postbronchodilator FEV1 of 1.40 L, 64.6% predicted) and a severely reduced DLCO (8.38 mL/min/mm Hg, 38.4% predicted). Results of a cardiac stress test do not show any ischemia. Her chest CT scan showed mild emphysematous changes diffusely. Her hemoglobin concentration was normal.

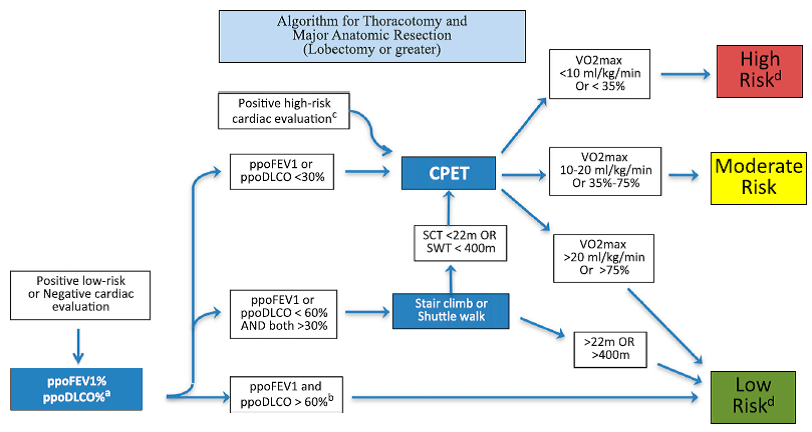

Which of the following is the best next test in her treatment evaluation?

A. A left-sided heart catheterization

B. A cardiopulmonary exercise test

C. A right-sided heart catheterization

D. A 6-min walk test

B. A cardiopulmonary exercise test

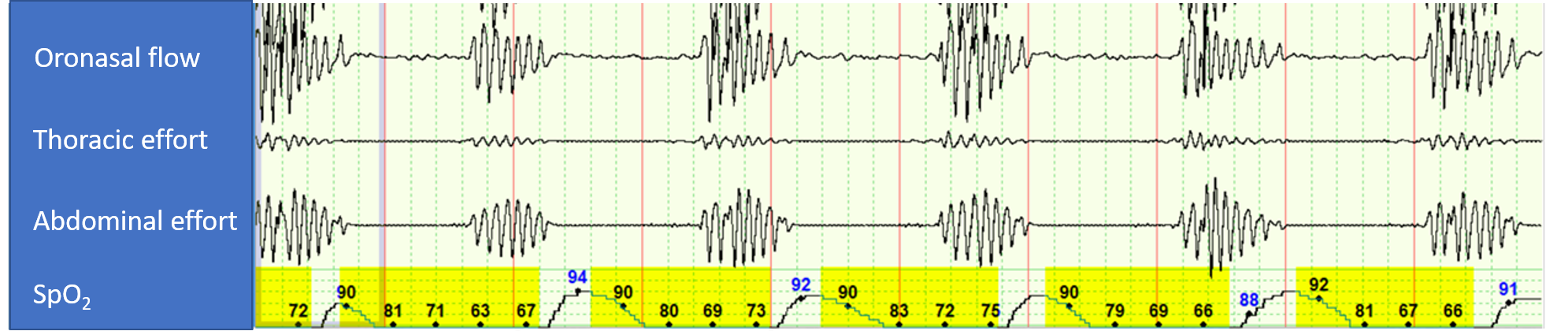

The 5-min polysomnographic recording in Figure 1 is from a CPAP titration study in a patient with history of atrial fibrillation (normal echocardiogram with left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% while in atrial fibrillation) and moderate OSA. During this portion of the study, the patient is on CPAP of 4 cm H2O.

Which of the following interventions by the sleep technologist is most likely to resolve the respiratory abnormality observed in Figure 1 during the PAP titration polysomnogram?

A. Increase CPAP setting.

B. Decrease CPAP setting.

C. Switch to adaptive servoventilation.

D. Switch to bilevel PAP spontaneous mode (without a backup rate).

C. Switch to adaptive servoventilation.

Patient with OSA + atrial fibrillation

On CPAP 4 cm H₂O → OSA resolved but severe central sleep apnea (CAI 55/hr) emerged

Diagnosis: Treatment-emergent central sleep apnea (TECSA)

In OSA with TECSA, check EF first.

If EF ≥45% → ASV is best

If EF <45% → avoid ASV, consider CPAP continuation, oxygen, acetazolamide, or phrenic nerve stimulation

A 48-year-old man is admitted to the hospital after having 1 to 2 months of progressive dyspnea on exertion, cough, and unintentional weight loss. He is an active tobacco user and has smoked 1 pack per day for the past 28 years. His medical history is notable for hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, nonobstructive coronary artery disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. His home medications include carvedilol, metformin, amiodarone, and atorvastatin. Regarding his symptoms, he reports that over the past few months he has noted increasing shortness of breath and nonproductive cough. This has progressed to the point that he is dyspneic even with daily tasks. He has lost 10 lb (4.54 kg) unintentionally over this time. He denies any fevers, night sweats, chills, sick contacts, lymphadenopathy, or recent travel.

In the hospital, he is noted to be hypoxemic breathing ambient air. His physical examination reveals bilateral lower lobe crackles, and he has an abnormal chest radiograph, so a chest CT scan is obtained (Figure 1).

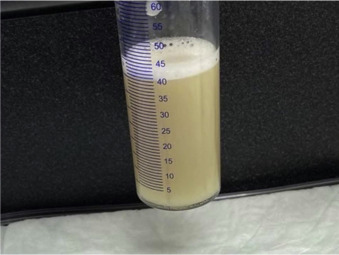

On the basis of the CT scan findings, the patient undergoes bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) that yields a large amount of milky white material (Figure 2).

What BAL findings would help confirm the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

A. Large foamy macrophages with increased levels of phospholipids in the BAL fluid

B. Lymphocyte predominance with an elevated ratio of CD4+ to CD8+ >4

C. Positive staining for CD1a and S100

D. Enlarged alveolar macrophages with acellular proteinaceous material and diffusely positive periodic acid-Schiff staining

D. Enlarged alveolar macrophages with acellular proteinaceous material and diffusely positive periodic acid-Schiff staining

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP) confirmed by:

Clinical features (indolent, progressive dyspnea/cough).

HRCT: crazy-paving pattern (ground-glass opacities + septal thickening).

BAL fluid: milky white appearance, engorged macrophages, PAS-positive proteinaceous material.

Amiodarone toxicity: foamy macrophages in BAL, nonspecific. ❌ Choice A.

- Sarcoidosis: BAL lymphocytosis with high CD4+/CD8+ ratio >3.5. ❌ Choice B.

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis: BAL positive for CD1a and S100 (Langerhans cells). ❌ Choice C.

One of the health care providers on your team was exposed without adequate personal protection to an acid-fast bacilli smear-positive patient with multidrug-resistant TB. The antimicrobial susceptibilities reveal resistance to isoniazid and rifampin. After initial evaluation, the health care provider is found to have no symptoms, the chest radiograph shows no pulmonary infiltrates, and both the tuberculin skin test and the interferon-γ release assay are negative. What is the best next step in the care of this health care provider?

A. Observe and repeat testing if symptoms appear.

B. Start levofloxacin.

C. Start pyrazinamide/moxifloxacin.

D. Start intensive phase treatment with at least 5 drugs.

B. Start levofloxacin.

Treat presumed MDR LTBI even if TST/IGRA initially negative.

- Without therapy: ~14.3% develop active MDR TB.

- With therapy: ~1.1% develop active MDR TB.

First-line regimen

Later-generation fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin)

± second agent (ethambutol or ethionamide, depending on susceptibility).

Duration: 6–12 months.

Monitor closely for adverse effects of fluoroquinolones (GI upset, QT prolongation, tendinopathy).

Duration of prophylaxis is longer than for drug-susceptible LTBI.

A 67-year-old current 40-pack-year smoker was found to have mild polycythemia on lab work performed during evaluation of chronic sinusitis. As part of her evaluation, chest imaging was performed, revealing a solid 1.5-cm spiculated nodule in the apex of the right upper lobe (Figure 1). The nodule was fluorodeoxyglucose avid on PET imaging, with a standard uptake value of 7.8 and no evidence of regional or distant spread. A transthoracic needle biopsy showed a lung adenocarcinoma. A second smaller nodule was seen in the periphery of the right lower lobe, too small to sample (Figure 2). Her cardiopulmonary assessment revealed a moderate risk for pulmonary complications from a lobectomy. A wedge resection of the right apex was performed. Intraoperatively, the smaller peripheral right lower lobe nodule was also identified, and a wedge resection of this nodule was performed. It also revealed an adenocarcinoma. Hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes sampled during her surgery did not show any evidence of regional spread.

What is the stage of her cancer?

A. Cannot determine

B. T3N0M0, stage IIB

C. T4N0M0, stage IIIA

D. T1bN0M0, stage IA2 and T1aN0M0, stage IA1

A. Cannot determine

Comprehensive histologic and molecular characterization is required to distinguish separate primaries from intrapulmonary metastases.

Separate tumor nodules of the same cancer

Same histology, same genomic profile.

Staged based on location:

T3 → same lobe.

T4 → different lobes, same lung.

M1a → contralateral lung.

![]()

A 19-year-old man with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) who is nonambulatory at baseline is admitted to the ICU with pneumonia and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. On the fifth hospital day, he is successfully extubated and is placed on nocturnal assisted noninvasive ventilation. He is transferred to the medical wards the next day. You are asked to assist with this patient's management prior to discharge home 2 weeks after admission.

On physical examination, his pulse and BP are normal. SpO2 is 95% on room air while awake. He has severe diffuse proximal muscle weakness with hypotonia and areflexia, as well as marked lumbar lordosis.

The patient has tolerated and been adherent with nocturnal assisted noninvasive ventilation since his extubation 10 days prior. Arterial blood gas and pulmonary physiologic test results obtained while the patient is awake on room air on the day of discharge are as follows: pH 7.37, PaCO2 51 mm Hg, and PaO2 68 mm Hg; vital capacity 49% predicted; maximum inspiratory pressure 62 cm H2O; and maximum expiratory pressure 59 cm H2O.

In preparation for discharge, in addition to daily lung volume recruitment, mucus mobilization, and mechanical cough assist maneuvers, which intervention should be recommended?

A. Nocturnal assisted noninvasive ventilation

B. Nocturnal and daytime assisted noninvasive ventilation

C. Tracheostomy

D. Nocturnal supplemental oxygen at 2 L/min

B. Nocturnal and daytime assisted noninvasive ventilation

Despite nocturnal NIV, the patient has daytime hypercapnia (PaCO₂ 51 mm Hg) → indication to extend NIV into waking hours.

Indications for nocturnal NIV:

Symptoms of hypoventilation (fatigue, morning headaches, dyspnea, hypersomnolence).

OR physiologic evidence: VC <50%, MIP <60 cm H₂O, awake SpO₂ <95%, PaCO₂ >45 mm Hg.

Daytime NIV:

Indicated if daytime SpO₂ <95%, PaCO₂ >45 mm Hg, or awake dyspnea.

This patient qualifies (PaCO₂ 51).

Choice A – nocturnal only NIV: ✗ Incorrect → patient already hypercapnic in daytime.

Choice B – nocturnal + daytime NIV: ✓ Correct → improves survival & quality of life.

Choice C – tracheostomy: ✗ Reserved for failed NIV, repeated failed extubation, aspiration due to bulbar weakness, or patient preference.

Choice D – nocturnal oxygen: ✗ Does not correct hypoventilation, may worsen CO₂ retention.

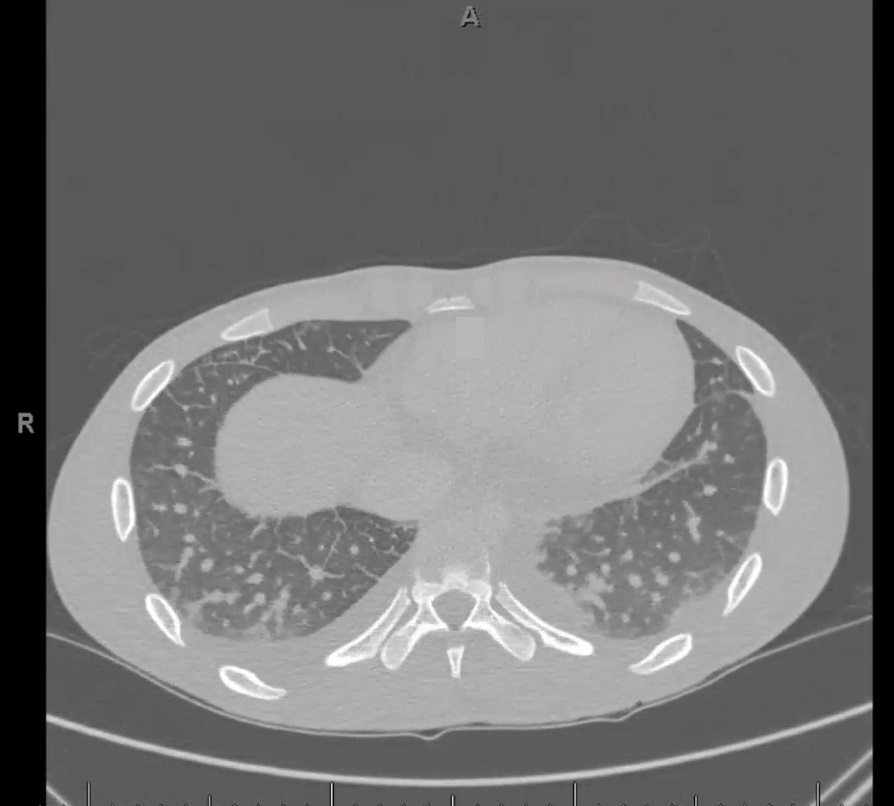

A 65-year-old man with a history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) whose joint symptoms are well controlled with methotrexate for the past 5 years presents to the emergency department with gastrointestinal symptoms. An abdominal CT scan is without abdominal disease but reveals interstitial abnormalities at the lung bases. The patient is then referred for pulmonary evaluation, and a high-resolution CT (HRCT) scan of the chest shows subpleural, basal predominant, reticular abnormalities with areas of traction bronchiectasis (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

The patient has a 15-pack-year history of smoking and stopped 5 years ago. He denies dyspnea on exertion or cough. Physical examination results are notable for articular changes consistent with RA and basilar lung crackles. Pulmonary function testing shows a mild reduction in both lung volumes and diffusing capacity. Spo2 is normal at rest. Serologic testing reveals a high rheumatoid factor (RF) level, negative anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody level, and negative results for other connective tissue diseases.

Which of the following should be done next?

A. Stop methotrexate.

B. Change to rituximab.

C. Begin nintedanib.

D. Maintain current therapy.

D. Maintain current therapy.

The patient has RA-ILD but is asymptomatic with stable disease → best management is to continue current therapy and monitor.

Methotrexate (MTX)

Historically linked to MTX pneumonitis (acute/subacute onset, GGO + air trapping on HRCT).

Now considered safe in RA-ILD and may be beneficial long-term.

Patient has tolerated MTX for years → should continue.

Alternative Options (if progression)

Rituximab: improves joint and ILD outcomes (retrospective evidence).

Mycophenolate mofetil: can be added.

Antifibrotics: for progressive fibrotic RA-ILD only.

You are asked to see a patient in the ED with abnormal chest CT findings. The patient is a 19-year-old college student at a Midwestern university previously in excellent health. He recounts the onset of a severe sore throat 2 weeks ago that was evaluated at student health services, and he was told that a throat swab taken at that time was “negative for Strep.” No antibiotics were prescribed.

His symptoms continued for days and were severe enough that he stopped eating solid foods and did not go to class. Over the past several days, the throat pain has been present but better, and he has been able to eat. Yesterday he felt feverish, had chills and rigors, and began to notice left-sided posterior chest pain with movement or deep breathing. This morning, a cough developed, and he first produced some brownish sputum and then a spoonful of bright red blood, after which he came to the ED.

On examination, he is febrile to 39 °C with heart rate of 120/min, respiratory rate of 18/min, and BP of 96/50 mm Hg. He has pain when trying to fully open his mouth, and his pharynx is erythematous with white exudates. His neck is tender bilaterally with possible lymphadenopathy but no distinct masses or fluctuance. The remainder of his examination is normal, but he reports left posterior chest pain when taking deep breaths for lung auscultation.

Initial laboratory data are notable for WBC count of 19,000 × 103/μL (19 × 109/L) with 26% bands. Chest CT angiogram with pulmonary embolus protocol was performed and revealed no pulmonary arterial clot, but there were abnormalities as shown in the representative image in Figure 1. Blood and throat cultures are pending, and he has been given 2 g of IV ceftriaxone. Transthoracic echocardiogram has been performed with adequate visualization of the valves, and no vegetations are seen.

What is the most appropriate next action?

A. Order transesophageal echocardiogram and begin vancomycin.

B. Add liposomal amphotericin B to current antibiotics.

C. Obtain thyroid function tests, including thyroglobulin level.

D. Order a neck CT scan and add metronidazole to current antibiotics.

D. Order a neck CT scan and add metronidazole to current antibiotics.

Lemierre Syndrome:

Septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein after an oropharyngeal infection.

Classic pathogen: Fusobacterium necrophorum (oral anaerobe).

Treat with:

Piperacillin–tazobactam, OR

Carbapenem (imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem), OR

Ceftriaxone + metronidazole.

- Differentials:

- 1. Staphylococcal septic emboli → from endocarditis/catheters (ruled out here).

- 2. Fungal pneumonia → inconsistent with history.

- 3. Metastatic thyroid carcinoma → not supported by risk factors or presentation.

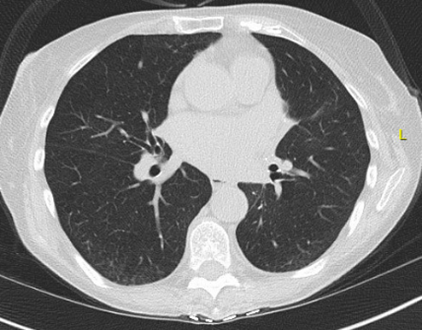

An 80-year-old man who has never smoked is seen at follow-up for evaluation of a lung nodule. He is currently able to walk one city block without dyspnea. He has a stable, mild chronic cough without sputum production. He does not have any chest pain, fevers, or constitutional symptoms. His medical history includes atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, OSA, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and benign prostatic hypertrophy. The most distant (Figure 1) and most recent (Figure 2) chest CT images, separated by 9 years, are shown.

Which of the following is the best next step?

(Figure 1)

(Figure 2)

A. Nonsurgical lung biopsy

B. Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET imaging

C. Surgical resection

D. Chest CT imaging surveillance

D. Chest CT imaging surveillance

Why Surveillance Is Correct

Pure GGNs often represent pre-invasive adenocarcinoma (AIS or minimally invasive adenocarcinoma).

As long as no solid component develops, risk of invasive cancer is low.

Growth in ground-glass component alone ≠ invasive transformation.

PET/CT is unhelpful → low FDG uptake due to indolent biology.

Nonsurgical biopsy is often low yield because of limited malignant tissue.

Guideline Recommendations (simplified)

Pure GGN <6 mm → no follow-up needed.

Pure GGN ≥6 mm → CT at 6–12 months, then q2 years up to 5 years if stable.

Part-solid GGN:

Solid <6 mm → CT at 6 months.

Solid 6–8 mm → CT at 3 months.

Solid >8 mm → manage like a solid nodule (consider biopsy/resection).

Trigger for escalation = development or enlargement of a solid component.