A 48-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with fatigue and lethargy. One month ago, she experienced fever, rash, and arthralgias that appeared the week after a backpacking excursion.

She has a heart rate of 39 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 80/42 mm Hg. She is not in respiratory distress. Her jugular venous pulse reveals intermittent large “a” waves. Her cardiac examination is notable only for bradycardia. She has no peripheral edema or rash. An electrocardiogram is obtained (figure).

In addition to placing pads on the patient’s chest for transcutaneous pacing, which one of the following next steps is most appropriate?

A. Administer ibutilide

B. Administer adenosine

C. Administer atropine

D. Perform synchronized electrical cardioversion

E. Place a temporary transvenous pacemaker

E. Place a temporary transvenous pacemaker

This patient’s electrocardiogram reveals complete heart block, which is likely to be caused by Lyme disease. Lyme-related carditis usually occurs within weeks to months of onset of infection and most often manifests as atrioventricular conduction block, with up to half of affected patients developing complete heart block.

In complete heart block, an obvious relationship between the P waves and the QRS complexes is not present, and a ventricular escape rhythm is evident. Large jugular venous “a” waves or “cannon a” waves are large venous pulse waves produced when the atrium contracts against a closed tricuspid valve; such dyssynchronous contractions of the atrium during ventricular systole can occur with complete heart block.

Management of symptomatic complete heart block depends on the acuity of the patient’s presentation:

• If the patient is in shock due to low cardiac output, transcutaneous pacing should be initiated immediately. Administration of dopamine or epinephrine may be reasonable as a temporizing measure while the clinician awaits the availability of a pacemaker.

• If the patient is somewhat more stable (as in this case), the clinician may prefer to hold off on transcutaneous pacing, given the discomfort associated with this intervention. Instead, the pacing pads can be placed on the patient’s chest so that if the patient’s clinical status deteriorates while arrangements for the transvenous pacemaker are being made, transcutaneous pacing can be initiated rapidly.

A 36-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with abdominal pain, a fever of 38.3°C, diarrhea, and hematochezia. One week earlier, she went on vacation to Mexico and had taken ciprofloxacin for prophylaxis against travelers' diarrhea. Her brother has been diagnosed with Crohn disease.

The patient’s vital signs are stable. Her abdominal examination reveals slight tenderness without any rebound or guarding. A plain-film radiograph of the abdomen is unremarkable. Stool cultures are negative for Shiga toxin and Clostridioides difficile toxin. A flexible sigmoidoscopy reveals diffuse colitis. Histologic review of a biopsy from the sigmoid colon demonstrates acute colitis with flask-shaped ulcers (figure) and no features of chronicity. Which one of the following treatments is most appropriate for this patient?

A. Oral glucocorticoid

B. Loperamide and a BRAT (bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast) diet

C. Azithromycin

D. Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole

E. Metronidazole followed by paromomycin

E. Metronidazole followed by paromomycin

Entamoeba histolytica — a parasite often seen in Central and South America, Africa, and Asia. This infection is characterized by the presence of flask-shaped enteric ulcers on microscopic evaluation of an intestinal biopsy. The most appropriate treatment of entamoeba infection is a course of metronidazole for the amebic colitis, followed by a luminal agent such as paromomycin to prevent recurrent infection. Paromomycin is not recommended as concurrent treatment with metronidazole because it causes diarrhea in many individuals.

- This patient had already taken a course of ciprofloxacin for prophylaxis against travelers' diarrhea, and a recurrence is unlikely. Thus, both ciprofloxacin and azithromycin would be inadequate.

A 45-year-old woman presents for her annual evaluation. She is asymptomatic, but her 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is estimated to be 15%. The physician recommends initiating treatment with rosuvastatin and low-dose aspirin. The patient mentions that her husband was recently diagnosed with Helicobacter pylori infection by a urease breath test and is currently undergoing treatment. She read online that the infection is associated with gastric ulcers and cancer. She requests testing for Helicobacter pylori infection. What is the most appropriate response to the patient’s request?

A. Recommend Helicobacter pylori antibody serology testing.

B. Recommend a fecal antigen test for Helicobacter pylori infection.

C. Empirically treat for Helicobacter pylori infection

D. Reassure the patient that Helicobacter pylori testing is unnecessary at this time

B. Recommend a fecal antigen test for Helicobacter pylori infection

• Active peptic ulcer disease or a history of peptic ulcer disease without prior H. pylori eradication therapy

• Uninvestigated dyspepsia

• Gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma

• Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer

• Unexplained iron deficiency anemia

• Immune thrombocytopenia in adults

• Individuals on chronic NSAID therapy

• Before the initiation of chronic low-dose aspirin therapy

• Adults who share a household with an individual who has been diagnosed with H. pylori infection by a nonserological test

When H. pylori testing is necessary, the tests with the highest positive and negative predictive values are the urea breath test and fecal antigen tests. Serological testing is not preferred as a first-line test to diagnose H. pylori infection in asymptomatic individuals because it cannot distinguish active from past infections and has a lower diagnostic specificity compared to other methods.

It is important to reassure the patient that while H. pylori infection is associated with ulcer disease and certain gastric malignancies — such as gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma — only a very small minority of infected patients develop these complications.

An 82-year-old woman hospitalized for Escherichia coli pyelonephritis is improving with the use of ampicillin when she experiences sudden onset of left-sided face, arm, and leg weakness. She reports no chest pain or shortness of breath.

Physical examination reveals findings consistent with an acute left hemiplegia and atrial fibrillation but is otherwise unremarkable. There are no carotid bruits.

The patient has been taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation for the past 20 years; her most recent international normalized ratio was 2.6. Results from a basic metabolic panel, urinalysis, and complete blood count are unremarkable.

CT of the head shows mild brain atrophy consistent with the patient’s age and no acute hemorrhage.

The patient is found to be hypertensive when vital signs are obtained in the first few hours after the onset of neurologic symptoms, and initiation of an antihypertensive medication is being considered.

What is the lowest blood pressure above which antihypertensive medications should be considered in this patient?

A. 220/120 mm Hg

B. 185/110 mm Hg

D. 140/90 mm Hg

The patient has symptoms consistent with acute stroke, and CT has ruled out a hemorrhage as the cause. Given that she is taking warfarin and her international normalized ratio is >1.7, she cannot undergo intravenous thrombolysis. Her symptoms should therefore be managed medically.

Blood pressure is frequently elevated after a stroke, which is thought to optimize perfusion to areas distal to the arterial occlusion. In fact, the lowering of blood pressure in the acute setting has been associated with clinical deterioration, and a permissive approach to blood-pressure control immediately after a stroke is therefore recommended.

Current guidelines permit initiation of antihypertensive therapy if the blood pressure exceeds 220/120 mm Hg, although the benefit of initiating or reinstating antihypertensive treatment in the first 48 to 72 hours is uncertain. In a patient who is not a candidate for thrombolysis, it is generally reasonable to set a goal blood-pressure reduction of 15% in the first 24 hours, unless the patient has other strong indications for blood-pressure lowering (e.g., decompensated heart failure).

Of note, a blood pressure >185/110 mm Hg is itself a contraindication to thrombolytic therapy. If a patient is otherwise a candidate for thrombolysis, the recommendation is to lower the blood pressure to <185/110 mm Hg so that thrombolytic therapy may be administered safely.

An 86-year-old woman with a history of hypertension, overactive bladder, and asthma presents for evaluation of short-term memory loss that she first noticed a few weeks ago. At baseline, she is independent in her activities of daily living and cognitively intact. She lives in the community with her husband and works part-time at the front desk of a museum. For the past 2 weeks, she has been feeling fatigued and has twice had to take a short afternoon nap to get through her workday. She has had difficulty concentrating on her work and almost forgot about a meeting with her supervisor, even though she is normally meticulous with her calendar and never misses a meeting. Two days ago, she locked her keys in her car while going grocery shopping and needed to call her daughter for help. She reports no changes in her sleep or mood and no recent falls or head trauma.

Her prescription medications include an albuterol inhaler and amlodipine. One month ago, she was also started on mirabegron for overactive bladder and was advised to try over-the-counter loratadine for nasal congestion from seasonal allergies. Her urinary and nasal symptoms are now well controlled.

Physical examination, including neurologic examination, is unrevealing. A basic metabolic panel, vitamin B12 assessment, and thyroid-stimulating hormone level are all within normal limits.

The patient scores 26 out of 30 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA).

What is the most appropriate next step in this patient’s care?

A. Discontinue mirabegron, and recommend nonpharmacologic management with bladder training

B. Replace loratadine with nasal fluticasone

C. Provide reassurance, and repeat the MoCA in 6 months

D. Start donepezil

E. Replace mirabegron with oxybutynin

Although this patient’s score on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is within the normal range, it is lower than expected given her high baseline cognitive reserve. Evaluation of new cognitive concerns should include a medication review, with consideration given to deprescribing medications that are known to have adverse cognitive effects. In this case, loratadine is the most likely culprit.

Loratadine is a second-generation antihistamine with activity against the histamine-2 receptor. Although it is less anticholinergic and less sedating than other antihistamines, any medication with anticholinergic adverse effects confers a risk of cognitive changes in older adults. For instance, loratadine appears on the Anticholinergic Risk Scale as a level 2 (out of 3), meaning that it has a moderate risk of contributing to adverse anticholinergic effects such as confusion. Recent initiation of this medication coinciding with new cognitive changes is highly concerning for an adverse drug effect, and first-line management is a trial of deprescribing.

An 18-year-old man presents to the emergency department after experiencing a witnessed syncopal episode that lasted a few seconds while he was at soccer practice. He remembers having dyspnea, palpitations, and chest pain before the episode. There was no injury or trauma. He reports no incontinence or confusion but states he was a little tired after the incident.

The patient appears comfortable. His heart rate is 68 beats per minute, his respiratory rate is 12 breaths per minute, his blood pressure is 132/84 mm Hg, and his oxygen saturation is 99% while he breathes ambient air. He has normal first and second heart sounds with a crescendo-decrescendo systolic murmur, best heard at the left sternal border, that increases with the Valsalva maneuver.

An electrocardiogram is obtained (figure).

What is the most likely cause of this patient’s syncopal event?

A. Athletic heart syndrome

B. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

C. Bicuspid aortic valve

D. Eisenmenger syndrome

E. Long-QT syndrome

B. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic disorder that is one of the most common causes of sudden cardiac death (SCD) among young people in the United States. The most common presenting symptom is dyspnea, but palpitations, chest pain, syncope, orthopnea, and dizziness can also occur. SCD in an athlete can be a manifestation of HCM.

Patients with HCM characteristically have normal first and second heart sounds with a crescendo-decrescendo systolic ejection murmur. The murmur is softer with an increase in preload (e.g., from squatting) and louder with a decrease in preload (e.g., performing a Valsalva maneuver).

With HCM, little difficulty exists during early systole in ejecting the blood through the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) into the aorta; therefore, the carotid upstroke is brisk. As systole progresses, LVOT obstruction occurs, resulting in a collapse in the pulse and then a secondary rise as LV pressure increases to overcome the obstruction. This sign is known as a bisferiens, or spike-and-dome, pulse. In contrast, because the fixed obstruction of aortic stenosis or a subvalvular aortic membrane is present during the entire cardiac cycle, the carotid upstroke in these entities is the classic parvus et tardus pulse, a carotid pulse with delayed amplitude and upstroke. Therefore, if any patient carrying a diagnosis of HCM has decreased carotid pulses, it should prompt thoughts of a mistaken diagnosis and further investigation into a fixed obstruction of the LVOT.

This patient’s electrocardiogram shows left ventricular hypertrophy with a left ventricular strain pattern (downsloping ST-T changes and T-wave inversion in anterolateral leads, I, aVL, and V4–V6), which is typical of HCM. An echocardiogram and genetic testing can help to confirm the diagnosis.

- Athletic heart syndrome (AHS), a benign condition in athletes, is a nonpathological heart adaptation to prolonged exercise training. It is usually found incidentally. Physical examination is typically unremarkable other than sinus bradycardia.

An 83-year-old woman with a history of hypertension is brought to the emergency department after she was found at home, confused and unable to get out of bed. Approximately 2 weeks ago, she attended a picnic with her church group in a wooded area and ate some undercooked barbecued fish and meat. A few days later, she developed a fever, headache, and joint pains. She became increasingly weak and needed to use a walker.

On physical examination, her temperature is 38.8°C, her heart rate is 98 beats per minute, and her blood pressure is 145/87 mm Hg. She is disoriented and requires constant stimuli to stay alert. The rest of her neurological examination shows facial diplegia, diffuse weakness, and areflexia. No signs of meningismus or sensory deficits are noted. She is unable to walk.

She is up to date with Covid-19 vaccinations, and testing for SARS-CoV-2 is negative. Laboratory examination of the cerebrospinal fluid yields the following results: Erythrocyte count 0, Leukocyte count 80 (lymphocytic predominance), Protein 70, Glucose, 68

Which one of the following diagnoses is most likely in this case?

A. West Nile virus encephalitis

B. Guillain-Barré syndrome

C. Lyme disease

D. Neurocysticercosis

E. Scrombroid poisoning

A. West Nile virus encephalitis

Fever, altered mental status, and flaccid paralysis with areflexia in the absence of sensory findings are typical characteristics of West Nile virus encephalitis, a poliomyelitis-like illness. Testing of the cerebrospinal fluid typically shows a lymphocytic pleocytosis. Most patients with West Nile virus infection remain asymptomatic; some develop a self-limited viral illness with headache, malaise, and myalgia. However, patients who are older than age 50 and those who are immunosuppressed are at increased risk for meningoencephalitis and neuroinvasive disease involving the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome can also manifest with weakness, but it is not typically associated with pleocytosis, encephalitis, or fever.

- Lyme disease is usually no associated with paralysis and arreflexia

- Neurocysticercosis is caused by the pork tapeworm Taenia solium in its larval stage. This organism is transmitted among humans primarily via the fecal-oral route, whereby eggs shed in the feces of a person with an active tapeworm infection are ingested by another person and then hatch into larvae that can penetrate the intestinal wall and reach a variety of tissues where they form cysts. Neurocysticercosis is characterized by seizures (in 80% of patients) and rarely involves the peripheral nerves. Patients are typically afebrile.

- Scrombroid poisoning occurs from consuming inappropriately refrigerated or preserved fish, but it usually manifests as an allergic-type reaction (including flushing and urticaria) within an hour of consumption.

A 45-year-old man with a history of Crohn disease has had nonbloody diarrhea for the past 6 weeks. Two months ago, he underwent resection of 50 cm of his ileum after developing a small-bowel obstruction related to an ileal stricture. He denies abdominal pain or fevers. His only medication is azathioprine. On examination, his abdomen is soft and nontender. Laboratory studies reveal a normal leukocyte count and no evidence of anemia. An abdominal CT scan does not show any bowel-wall thickening. Which one of the following treatments is most appropriate for this patient's diarrhea?

A. Cholestyramine

B. Vancomycin

C. Prednisone

D. Gluten-free diet

E. Teduglutide

A. Cholestyramine

Bile acids undergo enterohepatic circulation and are absorbed primarily in the ileum. Bile salt malabsorption occurs if the ileum is damaged or removed. If <100 cm of ileum is removed, the liver compensates with increased bile acid production, and fat absorption remains normal. However, the unabsorbed bile acids stimulate electrolyte and water secretion in the colon, leading to secretory diarrhea. Treatment with a bile acid-binding resin, such as cholestyramine, can reduce the diarrhea. If >100 cm of ileum is removed, the liver cannot compensate, and steatorrhea occurs. In this situation, the addition of a bile acid-binding resin can reduce the already depleted bile acid pool and increase symptoms by increasing fat malabsorption.

A 78-year-old woman with a history of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia is brought to the clinic by her daughter. The daughter reports that since last seeing her mother one year ago, her mother is slower to accomplish things around the house, lacks initiative, and walks more slowly. The patient reports no feelings of depression, recent illnesses, or hallucinations. Her blood pressure was suboptimally controlled in the past, but she has been more adherent to her medications recently.

She scores 24 out of 30 on the Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination, indicating mild cognitive impairment. She lost points for calculation and orientation but had intact registration, immediate memory, delayed recall, and visuospatial construction. The rest of her neurologic examination is normal, except for a reduced gait speed.

Laboratory evaluation reveals normal vitamin B12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and a negative treponemal antibody test.

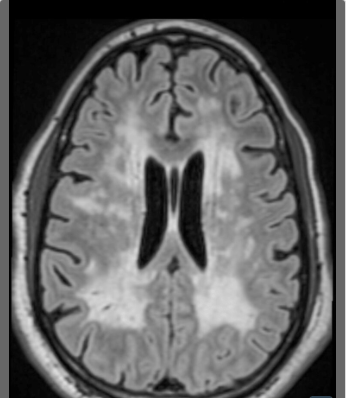

MRI of the brain reveals extensive confluent periventricular and temporal lobe white-matter hyperintensities (figure).

Which one of the following diagnoses is most likely in this patient?

A. Normal pressure hydrocephalus

B. Vascular cognitive impairment

C. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

D. Dementia with Lewy bodies

E. Alzheimer's disease

The diagnosis of vascular cognitive impairment can be established by demonstrating cognitive impairment along with either a history of clinical stroke or imaging that reveals features of cerebrovascular disease, such as diffuse periventricular white-matter intensities.

Periventricular white-matter hyperintensities have been most closely associated with vascular causes of dementia and predict an increased risk for stroke, cerebrovascular events, dementia, and death.

A 73-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and osteoarthritis of the knees presents with concerns about his memory. He is accompanied by his partner of 40 years, who reports that he needs constant reminders about current events and has lost interest in socializing with old friends because he has difficulty following conversations. He is independent in all activities of daily living, including showering, dressing, toileting, and eating; however, he depends on his partner for instrumental activities of daily living, including driving, medication management, food preparation, and money management. He has no history of traumatic brain injury and reports no feelings of depression or problems with sleep or hearing.

His current medications are lisinopril, simvastatin, and acetaminophen. He does not take any over-the-counter medications and does not drink alcohol.

His vital signs and neurologic examination are both normal. His score on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-2 is 1 out of 6, making depression unlikely.

His laboratory results — including differential blood count; kidney, liver, and thyroid function; electrolyte, glucose, vitamin D, and vitamin B12 levels; and rapid plasma reagin and HIV testing — are all normal, as is an MRI of the head.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment shows deficits in executive function and delayed recall; his final score is 18 out of 30 (≥26 is considered normal).

Which one of the following diagnoses is most likely in this case?

A. Medication adverse effect

B. Dementia

C. Major depressive disorder

D. Mild cognitive impairment

E. Delirium

This patient’s memory impairment is affecting his daily functioning to the point that he cannot perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), which require complex planning and thinking. He also shows signs of impaired social functioning. These findings raise concern for dementia (major neurocognitive disorder), which is defined as progressive cognitive impairment that has become severe enough to compromise the patient’s social functioning, occupational functioning, or both.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is one of many available screening tests to aid in diagnosing dementia in patients who present with memory concerns and functional decline. It assesses several cognitive domains including executive function, verbal fluency, attention, language, abstraction, delayed recall, and orientation. A score of ≤26 is considered abnormal and, in conjunction with other parts of a patient’s history, can help to determine the diagnosis.

This patient scored 18 on the MoCA, with demonstrated deficits in executive function and delayed recall. These findings, together with his history of functional impairment and the absence of an alternative explanation, are suggestive of dementia. Patients who have difficulty with executive function often demonstrate difficulty with IADLs that require planning and organization, such as medication and financial management.

When evaluating patients with memory impairment, clinicians should be sure to rule out other factors that could impair memory and function, including depression, thyroid dysfunction, electrolyte abnormalities (such as hyper- or hypocalcemia), vitamin deficiencies (mainly vitamin B12), underlying infections (such as syphilis), adverse effects of medications or toxins (such as benzodiazepines, opioids, antihistamines, muscle relaxants, and alcohol), and central nervous system pathology. In this case, the patient has a low likelihood of depression (given his normal score on the Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ]-2), although further workup with the PHQ-9 or the Geriatric Depression Scale could be considered. He is not taking any high-risk medications, he does not drink alcohol, and his other diagnostic studies do not suggest other causes of cognitive impairment.

A 63-year-old man develops acute chest pressure and respiratory distress 48 hours after undergoing emergency percutaneous revascularization for an anterior-wall myocardial infarction.

He has a blood pressure of 104/70 mm Hg, a regular heart rate of 167 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 91% while breathing ambient air. He has crackles in the bases of both lungs.

An electrocardiogram is obtained (figure).

Which one of the following management approaches is most appropriate for this patient?

A. Synchronized cardioversion

B. Metoprolol bolus

C. Verapamil bolus

D. Amiodarone bolus and infusion

E. Diltiazem bolus and infusion

A. Synchronized cardioversion

The first step in managing any tachycardia is to determine if the patient’s condition is stable or unstable. An unstable patient with a wide-complex tachycardia should be presumed to have ventricular tachycardia, and immediate cardioversion should be performed. Features of clinical instability include hypotension, a change in mental status, pulmonary edema (as in this case), and angina.

In a patient with a recent myocardial infarction, wide-complex tachycardia usually represents ventricular tachycardia. This patient’s electrocardiogram suggests ventricular tachycardia (not supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction) because it shows right bundle-branch morphology with a monophasic R wave in lead V1 and an R/S ratio < 1 in lead V6.

A 54-year-old man presents with a painless rash that first appeared on his right foot 8 months ago and has progressively moved up his leg. He was diagnosed with HIV infection more than one year ago, when he was admitted to the hospital for pneumocystis pneumonia, but he did not follow up after being discharged from the hospital. On physical examination, his right leg has multiple purplish-blue nodules and plaques of varying sizes associated with 1+ pitting edema. His CD4 count is 34 cells per mm3 (reference range, 400–1600). In addition to antiretroviral therapy, what is the best initial management option for this patient?

A. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin

B. Plasma exchange

C. Observation

D. Intramuscular penicillin G benzathine

E. Topical glucocorticoids

c. Observation

The presence of multiple purplish-blue skin nodules in a person with HIV is indicative of Kaposi sarcoma, an AIDS-defining malignancy. All people with HIV should be treated with antiretroviral therapy. If they have asymptomatic, localized Kaposi sarcoma, then initiation of therapy would be expected to cause the rash to recede as CD4-cell counts improve and HIV viral load declines. On occasion, there is transient worsening because of the enhanced inflammatory response associated with immune reconstitution. This process, termed the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, is most commonly seen in patients, such as this one, who have advanced HIV-related immunosuppression. Severe cases may require systemic chemotherapy, systemic glucocorticoids, or both. Despite the risk of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, combination antiretroviral treatment is clearly the first priority in this patient, both to control the Kaposi sarcoma and to prevent other HIV-related complications.

- Chemotherapies, such as pegylated anthracyclines, are often used to treat more advanced or visceral Kaposi sarcoma.

- Systemic glucocorticoids may have a role in the treatment of Kaposi sarcoma complicated by the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, but topical glucocorticoids are not used.

A 68-year-old woman who was previously found to have a 3-cm area of Barrett esophagus is reevaluated with surveillance endoscopy. She has gastroesophageal reflux disease that has been well controlled on omeprazole 40 mg twice daily for the past 3 years. She has not experienced any heartburn, dysphagia, or unintentional weight loss. She denies use of alcohol or tobacco. Chest and abdominal examinations are unremarkable and show no signs of lymphadenopathy. New biopsies from the affected area demonstrate low-grade dysplasia but no signs of esophagitis or hiatal hernia. Which one of the following next steps is most appropriate for this patient?

A. Refer for transesophageal endoscopic ultrasonography

B. Repeat endoscopy in 3 months

C. Refer for endoscopic ablation

D. Replace omeprazole with lansoprazole

E. Refer for endoscopic mucosal resection

C. Refer for endoscopic ablation

Patients with Barrett esophagus who have newly diagnosed low-grade dysplasia should have the pathologic diagnosis confirmed by an expert gastrointestinal pathologist given considerable interobserver variability in the interpretation of esophageal biopsies. If the diagnosis is confirmed, the patient can either be monitored with surveillance upper endoscopy, initially every 6 months (but not every 3 months), or undergo endoscopic ablation of the abnormal area. Ablation is usually performed using radiofrequency energy, although photodynamic therapy and cryotherapy are also options.

Recommendation:

Nondysplastic, Barrett esophagus <3 cm in length => Repeat upper endoscopy every 5 years

Nondysplastic, Barrett esophagus ≥3 cm in length => Repeat upper endoscopy every 3 years

Indefinite dysplasia, Barrett esophagus of any length => Confirmation by expert pathologist. Start or adjust proton pump inhibitor therapy, then repeat endoscopy in 6 months. If still present, then repeat endoscopy in 1 year

Low-grade dysplasia => Endoscopic eradication therapy is recommended with surveillance endoscopy performed at 1 year and 3 years, then every 3-5 years thereafter following eradication therapy. If patient prefers endoscopic surveillance, then endoscopy should be performed in 6 months, again in 12 months, and annually thereafter

High-grade dysplasia => Endoscopic eradication therapy with surveillance endoscopy performed at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months, then annually thereafter following eradication therapy. Endoscopic surveillance alone is not a recommended option

A 49-year-old woman presents with a one-day history of acute episodes of dizziness. She reports nausea without vomiting and feels generally weak but has no focal muscle weakness. She notes that the dizzy spells last about 15 seconds and always seem to be provoked by a change in her head position, including turning to her side in bed or gazing upward. The episodes are intense but resolve on their own, and she can prevent them by avoiding the head movements that trigger the spells.

On examination, the patient has a normal mental status with intact speech. Cranial-nerve, motor, and sensory examinations are unremarkable.

Observing the patient for nystagmus after which one of the following maneuvers is most likely to confirm the diagnosis?

A. Placing the head in extension and rotating it 45 degrees while the patient is sitting - and then having the patient lie down quickly on her back with her head held in extension

B. With the patient recumbent, rotating the head to the affected side and then having the patient sit up

C. Moving the head from left lateral flexion to right lateral flexion back to left lateral flexion

D. Bringing the patient from a supine to an upright sitting posture, while maintaining 45-degree rotation of the head

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a common disorder that manifests as brief (10- to 20-second) episodes of intense vertigo provoked by certain changes in head position or gaze. There are no focal neurological deficits on examination.

The diagnosis is established with the help of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver. With the patient sitting upright, the head is rotated approximately 45 degrees to the patient’s right. The patient is then helped to lie down quickly on their back with their head held in approximately 20 degrees of extension. This is usually done with the patient’s head hanging off the examination table, and their eyes are observed.

The test is considered positive for BPPV when there is a 2- to 10-second period of latency before the onset of rotational nystagmus, which would be upbeat and torsional, with the top poles of the eyes beating toward the lower (right) ear. When the patient sits back up, the nystagmus will often reverse direction in cases of BPPV involving the posterior semicircular canal.

A 74-year-old man who has dementia with Lewy bodies is brought in by his wife. She has noticed worsening of the patient's cognition, most notably in his short-term memory and his ability to navigate to the correct room in their house. The patient has been spending more time sleeping in the living room chair; when he is awake, he experiences hallucinations and agitation and has engaged in behavior that is threatening to others. Redirection, cognitive stimulation, and reorientation have not been effective.

Which one of the following treatments is indicated for this patient?

A. Clonazepam

B. Haloperidol

C. Levodopa-carbidopa

D. Risperidone

E. Donepezil

Striking deficits in cholinergic neurotransmission are seen in the brains of patients who have dementia with Lewy bodies (and are greater than those seen in patients with Alzheimer dementia); therefore, drugs enhancing central cholinergic function represent a rational therapeutic approach to this disorder. Donepezil, a cholinesterase inhibitor, has been shown to improve neuropsychological performance and reduce apathy and hallucinations in patients who have dementia with Lewy bodies and is frequently used for this purpose, although it has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

A 63-year-old woman with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease presents for preoperative evaluation before surgical repair of a torn right rotator cuff.

She develops exertional angina after approximately 30 minutes of brisk walking that resolves with rest; these symptoms have been stable for 2 years. She underwent an exercise single-photon-emission CT nuclear stress test 11 months ago, which revealed a small area of mild reversibility in the inferior wall. At that time, her left ventricular ejection fraction was 61%. She was managed medically, and her symptoms have been stable since. She denies dyspnea, leg swelling, or orthopnea.

Her current medications are aspirin 81 mg daily, atorvastatin 40 mg at bedtime, pantoprazole 40 mg daily, and metoprolol succinate 100 mg daily.

Her blood pressure is 123/72 mm Hg, and her heart rhythm is regular at a rate of 66 beats per minute. She has no murmurs or gallops on cardiac examination. The rest of her physical examination is unremarkable. In addition to continuing the beta-blocker and statin, which one of the following approaches is most appropriate for this patient's preoperative management?

A. Perform cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention for any significant lesions

B. Perform an exercise treadmill test without imaging

C. Perform an echocardiogram

D. No further evaluation is required; proceed to surgery

E. Perform a nuclear stress test

D. No further evaluation is required; proceed to surgery

Coronary revascularization before noncardiac surgery is not recommended in patients with stable ischemic symptoms and low-risk disease, given that randomized trials have shown no benefit of preoperative revascularization in reducing the risk for adverse cardiac events in these patients.

- Coronary revascularization should be considered before noncardiac surgery in patients with recent unstable angina or recent myocardial infarction. In addition, cardiac catheterization with coronary angiography should be considered for patients in whom recently progressive symptoms or recent noninvasive testing suggests a high probability of high-risk disease (e.g., significant left main coronary artery stenosis, three-vessel disease, or two-vessel disease with significant proximal left anterior descending artery stenosis); in some of those cases, angiography and possibly revascularization might be indicated independent of the noncardiac surgery. In this patient with long-standing stable angina and good functional status, there is no indication for performing a cardiac catheterization.

- In this patient with long-standing stable angina and good functional status, there is no indication for performing a treadmill test without imaging.

- Because the patient has no symptoms of heart failure and no physical findings consistent with severe valvular disease, an echocardiogram is unlikely to alter clinical management.

- In this patient with long-standing stable angina and good functional status, there is no indication for repeating a nuclear stress test.

A 19-year-old woman presents for a physical before starting at a university, where she will live in a dormitory. She immigrated to the United States from Brazil 4 years ago. She was hospitalized twice for fevers and “a heart condition” at ages 7 and 12. She has a pronounced first heart sound and a faint mid-diastolic murmur at the apex. A follow-up transthoracic echocardiogram shows mild left-atrial enlargement and a thickened calcified mitral valve suggestive of prior rheumatic heart disease. Which one of the following antibiotic regimens is most appropriate for reducing this patient’s risk for further cardiac complications?

a. Amoxicillin once daily for one year from the last attack

B. No preventive antibiotic treatment is indicated

C. Penicillin G benzathine intramuscular injection monthly until age

D. Cephalexin twice daily for 5 years after the last attack

E. Amoxicillin twice daily until age 21

C. Penicillin G benzathine intramuscular injection monthly until age 40

Acute rheumatic fever is a complication of pharyngeal infection with group A streptococcus (GAS). Rheumatic heart disease is rare in the United States but is the leading cause of cardiovascular death during the first five decades of life in the developing world.

Patients with a history of rheumatic fever who develop subsequent GAS pharyngitis are at high risk for recurrent attacks, with progression to rheumatic heart disease. GAS pharyngitis can be asymptomatic, so continuous antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent reinfection is recommended.

The duration of antibiotic therapy depends on the severity of disease and the risk for recurrence. Patients such as this one, who have a history of carditis and residual valvular disease, require preventive antibiotics for 10 years after the last attack or until age 40, whichever is longer.

People with a history of rheumatic fever and carditis without valvular disease should receive prophylactic antibiotics for 10 years after the last attack or until age 21, whichever is longer. People with a history of acute rheumatic fever without carditis should receive antibiotics for 5 years after the last attack or until age 21, whichever is longer. Teachers, healthcare personnel, military recruits, and others living in crowded situations (e.g., college dormitories) are at increased risk for exposure and recurrence.

The recommended antibiotics for secondary prevention of rheumatic fever include long-acting penicillin G benzathine intramuscular injections every 3 to 4 weeks, daily oral penicillin V, sulfadiazine, or a macrolide antibiotic, such as azithromycin.

A 78-year-old woman is seen in the emergency department for diffuse generalized abdominal pain that has gotten progressively worse during the past 4 days. She has not been seen in a health care setting in more than 20 years, but her son recalls that she was diagnosed with hepatitis B virus infection when she immigrated to the United States from Asia 30 years ago. On physical examination, she has a distended abdomen, with shifting dullness to percussion. She has mild abdominal tenderness to palpation, with voluntary guarding. She has mild scleral icterus and a normal neurologic examination, including a mental status assessment within normal limits.

Laboratory evaluation reveals a platelet count of 115,000 per mm3 (reference range, 150,000–350,000) and an alpha-fetoprotein level of 1420 ng/mL (reference range, <15). Her carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 level is not elevated. Her serum hepatitis B surface antigen and her serum hepatitis B core antibody are both reactive/positive.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis reveals a moderate amount of ascites, with a 4.3-cm mass in segment VII of the liver. The liver has imaging features consistent with a diagnosis of cirrhosis. There is no radiographic evidence of lymphadenopathy, adrenal mass, bony lesions, or peritoneal thickening.

A dedicated MRI of the liver shows a solitary 4.3-cm mass with enhancement on the late arterial phase of contrast administration and washout on delayed venous-phase imaging. A noncontrast CT of the chest shows no evidence of pulmonary metastasis.

Sampling of the patient’s ascites rules out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and cytology is negative for tumor cells.

What is the most appropriate next step in this patient’s care?

A. Order an ultrasound of the right upper quadrant

B. Perform a transjugular biopsy of the mass

C. Initiate treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma

D. Perform a percutaneous image-guided biopsy of the liver mass

E. Order 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose with positron emission tomography

C. Initiate treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) usually occurs in the setting of chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection. In the setting of chronic liver disease and an elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein level, the characteristic imaging findings of HCC are sufficiently specific and obviate the need for tissue diagnosis.

When HCC is suspected, a dedicated four-phase multidetector CT or dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI with late arterial-phase imaging is recommended. HCC manifests as a mass with enhancement and hypervascularity during the arterial phase and washout during the venous phase.

The preferred treatment for HCC is surgical resection, but many patients are ineligible for surgery because of the extent of their tumor or because of liver dysfunction. Liver transplantation is an option for a few patients. For patients who are not surgical candidates, the treatment options for HCC include local tumor ablation, transarterial chemoembolization, radiation therapy, and systemic therapy.

- A percutaneous image-guided biopsy is considered for liver masses >1 cm when the imaging findings are not characteristic of hepatocellular carcinoma or a hemangioma, when the patient is not considered high-risk for hepatocellular carcinoma, when the patient has elevated carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 with suspicion of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, or when the patient has cirrhosis outside the setting of the viral hepatidities.

A 26-year-old man is brought to the hospital after a first-time witnessed tonic-clonic seizure that lasted approximately 2 minutes. He has HIV and has been treated with combination antiretroviral therapy for 8 years. His HIV viral load has recently been undetectable, and his CD4 count is 350 cells per mm3 (reference range, 400–1600).

The patient is febrile and has a blood pressure of 120/85 mm Hg. He is confused and only able to follow two-step commands. He has neck stiffness, as well as weakness of the left face, arm, and leg. He has a conjugate gaze with symmetric, reactive pupils. The left arm and leg have increased tone, and he has an upgoing toe on the left.

Which one of the following acute management approaches is the most appropriate first step for this patient?

A. Prescribe a loading dose of intravenous phenytoin

B. Obtain blood cultures, and initiate treatment with vancomycin, ceftriaxone, ampicillin, acyclovir, and dexamethasone

C. Initiate treatment with fluconazole

D. Order CT head

E. Perform lumbar puncture

The first target should be treatment for possible bacterial meningitis, which must be managed expeditiously because it is potentially reversible and highly likely to cause morbidity. Blood cultures should be obtained without delay, and antibiotic therapy should be started immediately thereafter, with agents that cover probable bacterial pathogens and have good central nervous system (CNS) penetration. Adjunctive dexamethasone should be administered either simultaneously with or before the antibiotics, given its proven efficacy in reducing the complications of pneumococcal meningitis.

The presence of fever and neck stiffness is most concerning for a diagnosis of meningitis, and the focal findings with a seizure raise the possibility of a CNS mass lesion or infection. In general, one should obtain blood cultures and then initiate empiric antibiotic therapy for meningitis as soon as possible, and a lumbar puncture should be performed thereafter to obtain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). However, when focal findings are present that may suggest the presence of a mass lesion, or if a person is immunosuppressed, imaging of the brain with head CT is warranted before lumbar puncture in order to avoid possible consequent herniation. Such imaging is appropriate and should be arranged expeditiously.

An 84-year-old woman with a 5-year history of Alzheimer disease presents with her family for management of worsening symptoms, including memory loss, wandering, and decline in activities of daily living. She has been taking donepezil for the past year. The treatment initially improved her symptoms noticeably, but now her family is unsure whether she is continuing to benefit from the drug.

Provided that the patient and family wish to continue pharmacologic management, which one of the following approaches to drug therapy is the most appropriate next step for this patient?

A. Replace donepezil with vitamin E

B. Replace donepezil with quetiapine

C. Discontinue donepezil without adding a replacement

D. Replace donepezil with memantine

E. Continue donepezil

In the only large clinical trial to address further treatment of patients who had taken donepezil for months to years, patients were randomized to continue donepezil, stop donepezil, stop donepezil and start memantine, or continue donepezil and add memantine. During one year of observation, continuing donepezil was significantly better than stopping it, in the sense of a slightly slower average decline in cognition and function. Adding or substituting memantine did not confer any advantage over simply continuing donepezil. Thus, it would be reasonable to continue donepezil therapy in this patient. However, the decision to continue a medication depends on many factors, and it is unclear how long treatment should continue; in the aforementioned study, only about half the patients receiving donepezil were still taking it at one year.

A 51-year-old man with hypertension reports 6 months of intermittent fevers, progressive shortness of breath, orthopnea, fatigue, and chest pain.

On examination, his jugular venous pressure is normal, and he has faint bilateral crackles throughout both lung fields. He also has an early diastolic sound followed by a soft, mid-diastolic murmur at the apex. He has no conjunctival or skin lesions.

Which one of the following diagnoses is most consistent with this patient’s history and physical examination findings?

A. Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis

B. Mitral valve infective endocarditis

C. Subacute aortic dissection

D. Cardiac myxoma

E. Carcinoid syndrome

D. Cardiac myxoma

Cardiac myxomas are rare, benign, primary cardiac tumors that typically manifest with symptoms of cardiac obstruction (e.g., dyspnea, orthopnea), systemic inflammation (e.g., fever, weight loss), or embolization. They are most often found in the left atrium and can cause obstruction of the mitral valve, which may be identified on physical examination as a diastolic tumor plop and a diastolic murmur that mimics the murmur of mitral stenosis.

- Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis (marantic endocarditis) may manifest with signs and symptoms of systemic embolization. However, because the valvular lesions do not usually affect valvular function, they rarely cause significant murmurs.

- Infective endocarditis of the mitral valve typically causes a holosystolic apical murmur (due to regurgitation) and not an isolated diastolic murmur. Additional physical examination findings may also be present, such as Janeway lesions, Osler nodes, splinter hemorrhages, or conjunctival petechiae.

- Subacute aortic dissection would manifest as sharp chest pain with possible radiation to the back, not progressive shortness of breath or fevers.

- Carcinoid syndrome, associated with flushing and diarrhea, affects only right-sided valves unless an intracardiac shunt or a bronchial carcinoid tumor is present. This is because the noxious substances secreted by the carcinoid tumor reach the right side of the heart via the systemic circulation but are then inactivated in the pulmonary circulation, which thus protects the left side of the heart. This patient’s murmur is located at the cardiac apex and, therefore, is likely to originate from the mitral valve.

A 60-year-old male missionary reports one month of a nonproductive cough that began 5 days after he returned from a trip to Nicaragua. The cough is associated with fevers, chills, night sweats, myalgias, and mild shortness of breath. The patient reports no exposures to wild animals and no new sexual contacts, but he did stay in a hotel that was being remodeled. The patient’s vital signs are normal, and his physical examination is unremarkable. CT of the chest is obtained (figure). A subsequent lung biopsy reveals necrotizing granulomatous pneumonitis with numerous fungal organisms. What is the most likely diagnosis in this case?

A. Aspergillosis

D. Histoplasmosis.

Histoplasma capsulatum is endemic in Central and South America, so acute histoplasmosis should be on the differential diagnosis for travelers with new pulmonary symptoms who return from those regions. Acute histoplasmosis usually manifests as a flulike illness characterized by high-grade fever, chills, headache, nonproductive cough, and fatigue. Chest imaging often reveals diffuse reticulonodular infiltrates. Symptoms typically occur 1 to 3 weeks after exposure, and most affected patients recover spontaneously within 3 weeks. Treatment is usually unnecessary for mild-to-moderate disease. If symptoms last more than one month, itraconazole (200 mg three times daily for 3 days, then 200 mg once or twice daily for 6 to 12 weeks) is recommended.

- Aspergillosis is almost always seen in immunocompromised patients. It is generally a more indolent disease than histoplasmosis and has larger nodules, with an associated halo.

- Coccidioides immitis is also endemic to certain areas of Central and South America but is less prevalent than Histoplasma. Chest imaging is more likely to reveal a focal opacity, reticulonodular changes, or thin-walled, apical cavities.

- Blastomycosis is uncommon in Central and South America.

- Paracoccidioides brasiliensis is endemic in northeastern South America and in Central America. Paracoccidioides typically causes an asymptomatic primary pulmonary infection, but an acute disseminated infection may occur. Acute disseminated infections account for fewer than 10% of cases and are rare in adults over age 30.

A 68-year-old woman is seen for follow-up of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. Six months ago, she was started on chlorthalidone when her blood pressures were consistently elevated, and she was started on atorvastatin 20 mg daily when a fasting lipid panel revealed a total cholesterol level of 260 mg/dL (reference range, 125–200), an LDL-cholesterol level of 179 mg/dL (< 130), and an HDL-cholesterol level of 42 mg/dL (≥ 46). Before starting the chlorthalidone and atorvastatin, a comprehensive metabolic panel (including liver enzymes and fasting blood glucose) was normal. The patient has a family history of coronary artery disease. She does not consume alcohol, and she quit smoking several years ago. She feels well and takes no other prescription or over-the-counter medications.

Her current laboratory findings are as follows: AST 74, ALT 83, Alkaline phosphatase 88, Total bilirubin 0.9, LDL cholesterol 110.

Which one of the following management approaches is most appropriate for this patient?

A. Replace atorvastatin with pravastatin

B. Replace chlorthalidone with hydrochlorothiazide

C. Replace atorvastatin with fenofibrate

D. Halve the dose of atorvastatin

E. Continue with current medications

E. Continue with current medications

Asymptomatic elevations in alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase, up to three times the upper limit of normal, are seen in less than 1% to 3% of patients taking statins. Thus, the patient's current medications should be continued. Marked aminotransferase elevations (more than five times the upper limit of normal) with or without fever, myalgias, and jaundice indicate true hypersensitivity.

Data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System for 2000 to 2009 found statin-associated serious liver injury to be extremely rare (≤ 2 cases per one million patient-years). In addition, the National Lipid Association Statin Safety Task Force found no benefit of routinely monitoring liver function tests. Given these recommendations, prescribing guidelines and drug safety labels recommend assessing liver enzymes before initiating statin therapy — but no periodic monitoring thereafter, unless clinically indicated.

A 47-year-old man presents with a left-sided retro-orbital headache that began earlier this morning and has not responded to acetaminophen. He also reports mild neck pain on the left side and mentions that his left eye looks “funny.” He has a history of infrequent, mild, bilateral, featureless headaches but is otherwise healthy and does not smoke.

His vital signs are unremarkable. On physical examination, his left eyelid hangs slightly lower than the right, and his left pupil is smaller when examined in a darkened exam room; the eye is not injected. Neurologic examination, including visual acuity, is otherwise normal. Neck range of motion is normal, with no meningismus. What is the most appropriate initial evaluation for this patient?

A. Magnetic resonance angiography of the neck

B. Slit-lamp examination of the eye

C. Diagnostic trial of 100% oxygen

D. Plain-film radiograph of the chest

E. CT of the brain

A. Magnetic resonance angiography of the neck

An episode of partial Horner syndrome with ipsilateral headache suggests a “spontaneous” extracranial carotid dissection, particularly if the patient has neck pain. Hematoma resulting in expansion of the vessel wall leads to dysfunction of the surrounding sympathetic plexus, located around the carotid bifurcation and proximal internal carotid artery. Soft-tissue and vascular imaging of the neck is diagnostic, and it will also assess for uncommon but potentially associated arteriopathies or other dissections. CT of the brain is useful only when intracranial pathology is suspected, but CT angiography of the neck would be able to make a diagnosis of dissection similar to that of magnetic resonance angiography.

- A cluster headache may manifest as a Horner episode and usually responds to 100% oxygen, but the pattern is one of brief, recurring headaches.

- Horner syndrome is always due to damage to the sympathetic nervous system, so a slit-lamp examination of the eye examining the retina, anterior chamber, and optic nerve would not be helpful.

- A chest radiograph could reveal a superior pulmonary sulcus (Pancoast) tumor or a widened mediastinum of an aortic dissection, but it is not helpful for an acute presentation that is inconsistent with tumor. A chest radiograph will also not identify carotid dissections.

- CT of the brain is useful only when intracranial pathology is suspected, but CT angiography of the neck would be able to make a diagnosis of dissection similar to that of magnetic resonance angiography.

An 80-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer (treated with mastectomy at age 60), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, bilateral cataract removal, and mild Alzheimer dementia presents to clinic accompanied by her son and daughter. They are concerned because she drove to the local grocery store yesterday and took 4 hours to get home. When asked about the incident, the patient explains that she forgot where she parked her car and had to ask a store clerk to help her find it; once they found the car, she had difficulty driving home because the sun had set. She ended up driving to a high school two towns away, where she had previously volunteered, before finally driving home. The patient’s son also reports that she has become more forgetful about her appointments during the past 6 to 12 months and sometimes starts cooking at the stove and forgets to return to it until the pot has boiled over.

A complete blood count, basic metabolic profile, and urinalysis performed 2 weeks ago at a local urgent care center, where the patient was evaluated for generalized fatigue, showed normal results, and the patient reports no new symptoms.

Cognitive function is assessed in the clinic with brief neuropsychological testing. The patient has difficulty completing the Trail Making Test, which suggests impairment in visual function, executive function, and task switching. A brief delirium screen is negative.

Which one of the following next steps is most appropriate for this patient?

A. Refer her for a driving-safety evaluation by a physical or occupational therapist, and counsel her not to drive until the evaluation is complete

B. Repeat a urinalysis to assess for an underlying urinary tract infection

C. Counsel the family that driving challenges are expected in the normal progression of dementia

D. Request a driving assessment for her at the government agency that issues drivers’ licenses, and counsel her not to drive until the evaluation is complete

E. Recommend that she retire from driving and that her car be removed from her custody

The most appropriate next step for this patient is to undergo a formal evaluation by a driving rehabilitation specialist and to refrain from driving until the evaluation is complete. Such evaluations are often conducted by physical or occupational therapists who specialize in driving safety and rehabilitation. These individuals are trained to understand how progressive medical conditions and aging can affect driving. The evaluation typically involves a personal medical history, medication review, cognitive function testing, and if appropriate, an on-road assessment. The evaluator can assess an individual’s adherence to traffic rules, responses to traffic flow and incidents, and use of strategies to compensate for medical conditions; they can then recommend interventions if rehabilitation is appropriate and feasible. For example, a patient may be able to continue to drive with appropriate remediation, such as daytime-only driving and use of geographic-navigation tools.

Older adults may also experience vision changes that affect driving, and a reevaluation of this patient’s vision is appropriate, even though she has already had cataract surgery. Glaucoma and macular degeneration can cause vision distortion and, eventually, loss of vision. Cataracts typically cause cloudy or blurred vision and sometimes double vision, worsened night vision, diminished contrast sensitivity, and difficulties handling glare (e.g., from oncoming headlights at night).