An 83-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia reports one year of cramping pain in her right thigh and calf that consistently occurs when she walks on flat ground for 90 meters or more. The pain promptly resolves when she stops walking and stands still. She notes mild bilateral lower-leg swelling that is maximal at the end of the day and resolves overnight. She also notes mild tingling in both feet. She has no dyspnea or back pain.

On examination, the patient has no jugular venous distention. Her lungs are clear, and no murmurs or gallops are present. She has symmetric mild pitting edema of both ankles and feet. No pulses are palpable in either foot. Neurologic examination reveals decreased sensation to light touch and pinprick in both feet, and there is normal strength in all muscle groups of both lower extremities. Deep-tendon reflexes are absent at both ankles and are normal at both knees. A straight-leg raising maneuver is negative. Which one of the following diagnoses best explains this patient’s leg pain?

A. Venous insufficiency

B. Neurogenic claudication secondary to lumbar spinal stenosis

C. Arterial claudication

D. Diabetic neuropathy

E. Lumbar disk herniation

C. Arterial claudication

In patients with exertional lower-extremity pain, it is important to differentiate arterial claudication from neurogenic claudication. Arterial claudication typically causes reproducible exertional lower-extremity pain that resolves promptly with the cessation of exercise. The ipsilateral dorsalis pedis and posterial tibial pulses are not usually palpable in patients with arterial claudication. However, many older patients with cardiovascular risk factors have nonpalpable pulses in both feet, regardless of whether they have exertional pain.

- The pain of neurogenic claudication (usually caused by lumbar spinal stenosis) often persists for a short time after the patient stops walking. Patients with lumbar spinal stenosis may note absence of pain when seated and improvement of symptoms when bending forward. Their physical examination may reveal asymmetric motor, sensory, and deep-tendon reflex findings in the legs.

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy due to a herniated disk usually causes back pain and leg pain at rest. Physical examination may reveal ipsilateral neurologic findings corresponding to the level of the herniated disk.

- This patient likely has a symmetric distal sensory polyneuropathy that is characteristic of diabetes mellitus. Although this type of diabetic neuropathy can be painful, it is typically bilateral, and it is not exertional.

- Mild dependent edema in the absence of a systemic cause suggests chronic venous insufficiency. Venous insufficiency is not painful unless it is severe or complicated by ulceration or infection.

A 60-year-old man with previously diagnosed hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and a 25-pack-year history of cigarette smoking presents for evaluation of heartburn. He has been taking omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily for the past 8 years, which has generally controlled his reflux symptoms, but he is now having heartburn after meals 2 to 3 nights weekly. He reports no nausea, vomiting, or weight loss. He recently underwent cardiac stress testing in the emergency department, which was negative. He has no family history of cancer and had a normal colonoscopy 2 years ago.

On physical examination, he has normal vital signs and is in no acute distress. His oropharyngeal examination is normal, and he has no cervical lymphadenopathy. Heart and lung sounds are normal. His abdomen is soft and nontender, and he has central adiposity.

In addition to increasing the patient’s proton-pump-inhibitor dose, which one of the following tests should be ordered?

A. Barium swallow study

B. Esophageal pH testing

C. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

D. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

E. Abdominal radiography

C. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

This male patient, who is age 60 with long-term gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms and a history of smoking, should undergo esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to evaluate for Barrett esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Current guidelines recommend considering such evaluation for men who have chronic (>5 years) and/or frequent (at least weekly) symptoms of GERD (heartburn or acid regurgitation) plus two or more of the following risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma:

• Age >50 years

• White race

• Central adiposity (waist circumference >102 cm or waist-to-hip ratio >0.9)

• Current or past history of smoking

• Confirmed family history of BE or esophageal adenocarcinoma in a first-degree relative

A 30-year-old man reports a mild throbbing pain in the front of his right knee. The pain started approximately 3 weeks ago and is present only on flexing of the right knee. The patient works as a plumber and occasionally jogs. He reports no recent trauma, and his walking is not affected. He has no medical history and takes no medications.

The patient's vital signs are normal. Physical examination reveals tenderness and mild edema in front of the patella. No effusion is present. The range of motion is normal, but pain is elicited with full flexion of the knee. Anterior and posterior drawer tests and a McMurray test are negative.

What is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

A. Meniscal tear

B. Anserine bursitis

C. Anterior cruciate ligament injury

D. Posterior cruciate ligament injury

E. Prepatellar bursitis

E. Prepatellar bursitis

Prepatellar and superficial infrapatellar bursitis are caused by irritation, inflammation, or infection of the prepatellar and superficial infrapatellar bursae, which are located anterior to the patella and the patellar tendon, respectively. Repetitively being on one’s knees can cause prepatellar bursitis, which frequently occurs in tile-layers, plumbers, housekeepers, and those who kneel for religious reasons. Additional causes of prepatellar bursitis include trauma, infection, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Signs of prepatellar or infrapatellar bursitis on physical examination include focal tenderness, warmth, and bursal swelling. Joint effusion, if present, is often small and secondary to the bursal inflammation (a process termed “sympathetic effusion”). If a large knee effusion is present, it suggests a concurrent articular process. Pain is often exacerbated by passive flexion of the knee, but extension is not impaired and is often a preferred position because intrabursal pressure is at its lowest.

A 53-year-old woman presents with acute onset of bulky bilateral neck masses. On examination, she is tachycardic and febrile. She has bulky cervical and axillary adenopathy. Initial results from a bedside fine-needle aspiration biopsy reveal atypical cells consistent with high-grade lymphoma.

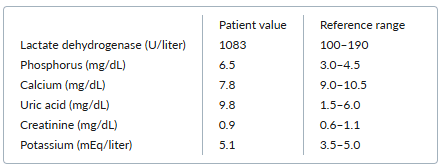

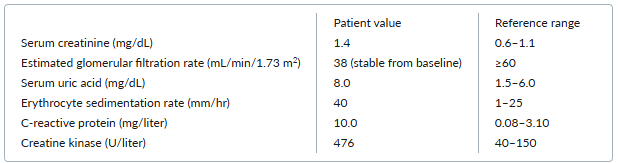

Selected initial laboratory results are as follows:

The patient is started on chemotherapy for her lymphoma and also on allopurinol. In addition, she is given normal saline for aggressive volume expansion that results in urine output of 150 to 200 mL/hour.

After 24 hours, her uric acid level is 13.2 mg/dL, and her serum creatinine level is 1.3 mg/dL. Her physical examination is unchanged with no evidence of volume overload.

Which one of the following treatments should be added to this patient’s regimen?

A. Furosemide

B. Hemodialysis

C. Rasburicase

D. Febuxostat

E. Urinary alkalinization

C. Rasburicase

This patient has tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) from high-grade lymphoma and is at high risk for further cell lysis as she continues chemotherapy.

TLS is the most common emergency associated with hematologic malignancies. The characteristic laboratory abnormalities are hyperuricemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and hyperkalemia. TLS can progress to kidney failure, cardiac arrhythmias, seizures, and death from multiorgan system failure.

Morbidity from TLS is reduced by establishing and maintaining a high urine output and reducing the serum uric acid level. The first steps are aggressive intravenous volume expansion with a target urine output of 80 to 100 mL/m2 /hour (150 to 200 mL/hour in most adults) and initiation of allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor that prevents uric acid formation. Together, these two interventions usually result in sufficient lowering of serum uric acid to prevent renal complications.

However, in patients at high risk for TLS and in those with active TLS (as in this case), volume expansion and allopurinol alone are insufficient to result in rapid lowering of the serum uric acid level. Rasburicase should also be added, as it can rapidly lower the serum uric acid level to prevent precipitation of urate crystals in the tubules and resulting renal failure.

A 72-year-old woman presents for preoperative evaluation before hip arthroplasty. She reports only hip pain with no chest pain, shortness of breath, or syncope.

Physical examination reveals a high-pitched click after S1, followed by a late-systolic murmur at the apex. S2 has normal physiologic splitting. The lungs are clear, and there is no peripheral edema.

Which one of the following conditions is the most likely cause of this patient’s cardiac examination findings?

A. Atrial septal defect

B. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

C. Mitral valve prolapse

D. Aortic regurgitation

E. Tricuspid regurgitation

C. Mitral valve prolapse

This patient’s physical examination findings are most consistent with mitral valve prolapse. The characteristic finding of mitral valve prolapse is a high-pitched, mid-systolic click related to tensing of the mitral valve as the mitral leaflets prolapse into the left atrium during systole. Often, as in this patient, the click is followed by a mid- or late-systolic murmur corresponding to some degree of mitral regurgitation, usually mild. The majority of patients with mitral valve prolapse have no symptoms. Although this patient is asymptomatic and does not have evidence of heart failure on examination, an echocardiogram would be recommended to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out other diagnoses that would have greater clinical implications, such as mitral regurgitation. A diagnosis of mitral valve prolapse would have no implications on this patient’s plans for surgery.

A previously healthy 42-year-old-man reports 2 days of diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal cramping after a one-week trip to Mexico with his family. He has five to six bowel movements daily, which alleviate the cramping. He also has chills and sweats. He is able to eat but only simple foods. The family members who traveled with him have not gotten sick. He is concerned about missing work because of the ongoing diarrhea.

He is hemodynamically stable and has a temperature of 39.4°C. He has normoactive bowel sounds and mild, diffuse abdominal tenderness to palpation but no distention, rebound, or guarding. On rectal examination, he is found to have blood in his stool.

A stool sample is sent for culture, and the patient is given oral rehydration.

While awaiting the results of the stool culture, which one of the following management approaches is most appropriate for this patient?

A. Prescribe trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

B. Prescribe azithromycin

C. Prescribe metronidazole

D. Prescribe amoxicillin

E. Do not initiate antimicrobial therapy, but send a stool sample for evaluation for ova and parasites

B. Prescribe azithromycin

In immunocompetent adults with bloody diarrhea, empiric antimicrobial therapy while study results are pending is recommended only in the following two scenarios:

• The patient is ill and has fever documented in a health care setting, abdominal pain, and other signs or symptoms of dysentery (e.g., frequent scant bloody bowel movements, abdominal cramps, tenesmus).

• The patient has recently traveled internationally and has a temperature ≥ 38.5°C, signs of sepsis, or both.

This patient fulfills both criteria as he has fever and abdominal pain — and has also traveled internationally. Therefore, providing empiric antimicrobial therapy would be reasonable for this patient while awaiting his culture results and ensuring adequate hydration.

Fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin) and azithromycin have been common choices for empiric therapy in this setting. However, azithromycin is now the preferred choice, given rising rates of microbial resistance to quinolones.

A 64-year-old man with hypertension and type 2 diabetes reports worsening back discomfort and bilateral leg pain when he walks his dog each day. He denies any recent trauma, sensory symptoms, or bowel or bladder incontinence but has noticed that the leg pain has worsened during the past few weeks. The pain now occurs after he walks only a few blocks, but it improves if he sits to rest or if he bends forward at the waist to walk uphill.

On physical examination, his pedal pulses cannot be appreciated, but his extremities are warm and well perfused. He is currently asymptomatic with intact strength, sensation, and reflexes in all four limbs. Vibration and proprioception are intact at the great toe. When he walks down the office hallway, he reports no pain and has a normal, narrow-based gait.

Which one of the following conditions is most likely to explain this patient’s pain?

A. Peripheral neuropathy related to diabetes

B. Radiculopathy related to a growing tumor

C. Impaired muscular blood supply related to peripheral vascular disease

D. Neurogenic claudication related to spinal stenosis

E. Myelopathy related to a bulging disk

D. Neurogenic claudication related to spinal stenosis

Spinal stenosis is a narrowing of the spinal column that can put pressure on the spinal cord and nerve roots, resulting in pain, numbness, and weakness. The most common cause is degenerative disease, typically occurring at the level of L3–4 and L4–5.

Spinal stenosis typically causes leg pain during walking and is relieved by rest, making it easy to confuse with leg pain that stems from other causes such as vascular insufficiency. However, patients with spinal stenosis typically describe pain that radiates down their legs or progressive weakness that is relieved with bending forward while walking, as this patient reports. Symptoms of vascular claudication stem from impaired muscular blood supply and are not typically relieved with changes in posture. Spinal stenosis often continues to cause pain when the patient is standing erect and still, whereas vascular claudication usually causes pain only when the patient is moving.

Aside from classic presenting symptoms, neurogenic claudication can be distinguished from vascular claudication with normal vascular studies and evidence of stenosis on spinal imaging (CT or MRI). Treatment for neurogenic claudication is typically conservative, including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and postural changes, although surgery may be considered in severe cases.

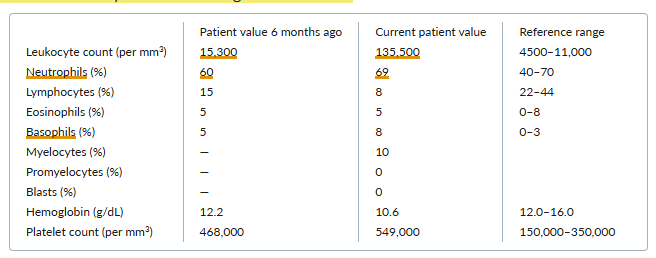

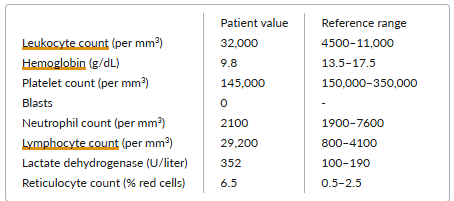

A 76-year-old woman reports a 2-month history of worsening fatigue and abdominal pain. She states that she has not had any fevers, chills, or recent infections.

On examination, she has splenomegaly and scattered ecchymoses on her lower extremities.

Laboratory results from both today and 6 months ago are as follows:

Which one of the following diagnoses is most likely in this case?

A. Leukemoid reaction

B. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

C. Acute promyelocytic leukemia

D. Acute myeloid leukemia

E. Chronic myeloid leukemia

E. Chronic myeloid leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) manifests with leukocytosis and a leukocyte differential that reflects the entire spectrum of the myeloid series. Absolute basophilia, eosinophilia, or both are often present. Thrombocytosis and splenomegaly are also often present. Although many patients are asymptomatic at presentation, typical symptoms include fatigue, malaise, weight loss, night sweats, and abdominal fullness or discomfort. Patients with <10% myeloblasts in the blood and bone marrow have chronic-phase CML. In contrast, patients with accelerated-phase CML have a blast count of 10% to 20%, and patients with CML in blast crisis (e.g., acute myeloid leukemia) have >20% blasts in the peripheral blood or bone marrow

A 71-year-old man presents for routine follow-up. He has a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis, and coronary artery disease.

Four months ago, he was hospitalized with a non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and a drug-eluting stent was placed in the left circumflex coronary artery. He has done well since the stent placement and is exercising several times per week with no cardiac symptoms. His hypertension is well-controlled. His current medications are metoprolol, lisinopril, simvastatin, metformin, aspirin, and ticagrelor.

He is eager to stop taking ticagrelor. He has not experienced any episodes of overt bleeding and is determined not to be at high risk of bleeding.

According to current guidelines, at least how long after drug-eluting stent placement must this patient wait to permanently discontinue ticagrelor safely?

A. 6 months

B. 3 months

C. 24 months

D. 12 months

E. 1 month

D. 12 months

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT; aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor such as clopidogrel, ticagrelor, or prasugrel) is recommended after stent placement to reduce the risk for stent thrombosis, an acute thrombotic occlusion within the stent that often causes ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The type of stent is a factor that influences the duration of DAPT. Late stent thrombosis (occurring > 1 month after the procedure) is more common with a drug-eluting stent (DES) than with a bare-metal stent (BMS). Other factors influencing the duration of DAPT include the reason for revascularization (acute coronary syndrome vs. stable ischemic heart disease) and the risk of bleeding.

Current (2021) guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) strongly recommend the following minimum durations of DAPT after stent placement:

• 1 month for a patient who has had a BMS placed for stable ischemic heart disease

• 6 months for a patient who has had a DES placed for stable ischemic heart disease

• 12 months for a patient who has had a stent (BMS or DES) placed for acute coronary syndrome

In patients who qualify for > 1 month of DAPT, an alternative approach (moderate recommendation) is to discontinue aspirin after 1–3 months and continue P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy. After 6 months of DAPT, the P2Y12 inhibitor can be interrupted briefly for elective surgery. If there is a high risk of bleeding, it may be reasonable (weak recommendation) to permanently discontinue the P2Y12 inhibitor 3 months after placing a DES for stable ischemic heart disease and 6 months after placing a stent for acute coronary syndrome.

In this patient who does not have a high risk of bleeding and had a stent placed for non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, ticagrelor can be safely discontinued 12 months after stent placement.

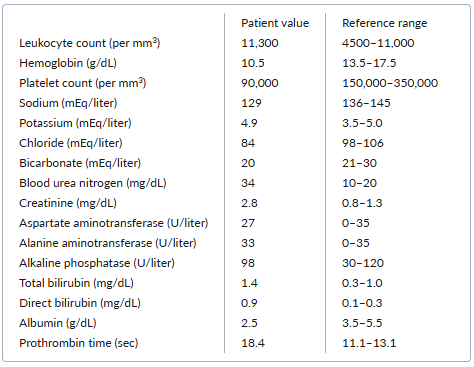

A 63-year-old man with a history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic low back pain, and chronic hepatitis C virus infection with decompensated cirrhosis presents to the emergency department with weakness, low-grade fevers, and fatigue for the past week. He reports no abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, melena, or hematochezia but does note reduced urine output.

His current medications are spironolactone 100 mg once daily, furosemide 40 mg once daily, insulin degludec 12 units daily, and acetaminophen occasionally for back pain. He reports no use of opioids or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

On physical examination, he appears well and is in no acute distress. His temperature is 37.4°C, his heart rate is 94 beats per minute, his blood pressure is 90/53 mm Hg, his respiratory rate is 16 breaths per minute, and his oxygen saturation is 96% while he breathes ambient air. He has moderate ascites, multiple spider angiomas on the chest, and mild asterixis.

Laboratory testing yields the following results:

One week ago, the patient’s blood urea nitrogen level was 12 mg/dL, and his creatinine concentration was 1.2 mg/dL.

Urinalysis with sediment is negative for red cells, white cells, protein, leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and casts. The urine sodium level is 5 mEq/liter (reference range varies with intake).

The patient is treated with one liter of normal saline. A diagnostic paracentesis is performed, and 50 mL of clear, straw-colored fluid is removed. Analysis of the ascites fluid reveals a neutrophil count of 700 per mm3 .

The patient is started on intravenous ceftriaxone and albumin for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and is admitted to the hospital, where these medications are continued. His home oral diuretics are held, and he is given additional intravenous albumin on the second hospital day. After 48 hours, his renal function has not improved.

In addition to continuing albumin, which one of the following next steps is most appropriate for managing this patient’s acute kidney injury?

A. Refer for renal replacement therapy

B. Refer for renal biopsy

C. Initiate treatment with a vasoconstrictor

D. Initiate treatment with intravenous furosemide

E. Perform large-volume paracentesis

C. Initiate treatment with a vasoconstrictor

This patient likely has hepatorenal syndrome (HRS). HRS occurs in the setting of cirrhosis and portal hypertension when an increase in vasodilatory factors leads to splanchnic vasodilation and a decrease in systemic vascular resistance. Splanchnic diversion of blood volume results in effective circulating volume depletion, which in turn leads to renal vasoconstriction and hypoperfusion.

HRS can be difficult to distinguish from diuretic-induced prerenal azotemia because laboratory results for the two conditions are similar; therefore, volume repletion should be given in the form of intravenous albumin (1 g/kg of body weight, up to 100 g per day) for at least 2 days. If the albumin does not correct the renal dysfunction, HRS is the likely diagnosis.

All of the following criteria must be met to make a diagnosis of HRS:

• Cirrhosis with ascites

• Diagnosis of acute kidney injury (an increase in serum creatinine of ≥0.3 mg/dL from baseline within 48 hours or ≥50% from baseline within 7 days)

• No response after 2 consecutive days of diuretic withdrawal and plasma volume expansion with albumin infusions (1g/kg of body weight per day)

• Absence of shock

• No current or recent use of nephrotoxic drugs (nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, aminoglycosides, or iodinated contrast media)

• No signs of structural kidney injury, as indicated by urine protein excretion >500 mg daily, urine red cell excretion >50 red cells per high-power field, or abnormal renal ultrasound

Treatment of HRS includes management of any underlying precipitants as well as therapy directed at the HRS itself. Precipitants of HRS include spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (as in this case), other infections, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is treated with antibiotics and intravenous albumin.

Initial medical treatment of HRS depends on the availability of medications. All patients should receive intravenous albumin and a vasoconstrictor. The first-line options for a vasoconstrictor are terlipressin and norepinephrine; the latter of which must typically be administered in an intensive care setting. An alternative treatment for patients who are not critically ill, and therefore not in an intensive care unit, is the combination of octreotide and midodrine. However, current evidence suggests that this combination is less effective than terlipressin or norepinephrine.

A 23-year-old woman reports a 2-week history of left-knee pain and swelling that started shortly after her last menstrual period ended. She also had fevers and migratory arthralgias during the initial 5 days, but those have since resolved. She has no past history of similar episodes.

She has a temperature of 37.6°C, a heart rate of 84 beats per minute, and a blood pressure of 124/70 mm Hg. The left knee, which is painful on both active and passive range of motion, is slightly warm to the touch. An effusion is present, but there is no overlying erythema.

Analysis of synovial fluid from the knee reveals a leukocyte count of 50,000 per mm3 with 80% polymorphonuclear cells, no crystals visualized on light microscopy, and negative Gram stain and culture.

Which one of the following diagnostic approaches is most appropriate for this patient?

A. Vaginal nucleic acid amplification assay for Neisseria gonorrhoeae

B. Complement CH50 blood testing

C. Factor VIII testing

D. Antinuclear antibody testing and rheumatoid-factor testing

E. Parvovirus serology testing

A. Vaginal nucleic acid amplification assay for Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Patients with disseminated gonococcal infection initially develop fevers, chills, and malaise. As the fever resolves, patients typically present either with a triad of tenosynovitis, dermatitis, and polyarthralgias or with frank arthritis. Overlap in these presentations is frequent. The tenosynovitis generally affects multiple tendons at once; the dermatitis often manifests as relatively few, transient pustular or vesicular skin lesions. Without treatment, patients who initially present with the triad will usually progress to joint involvement. The arthritis usually affects only a single joint, and the most common joints affected are the knees, wrists, and ankles.

The diagnosis of disseminated gonococcal infection is typically made from a positive blood or synovial fluid culture for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, but those cultures are positive in only about 50% of cases. Vaginal (or other urogenital), rectal, and pharyngeal cultures or nucleic acid amplification assays are positive in 50% to 80% of patients with disseminated gonococcal infection, even when the patients are asymptomatic at these local sites.

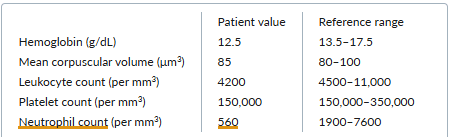

A 53-year-old man presents for a routine checkup. He feels fairly well and has not had any recent infections. He has a long history of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis with erosive disease. He previously required treatment with prednisone and methotrexate but has been off treatment for a year.

On physical examination, the patient’s spleen is palpable 3 cm below the left costal margin, but the abdominal examination is otherwise normal. There is no lymphadenopathy and no evidence of active synovitis.

Laboratory testing yields the following results:

The peripheral-blood smear is interpreted as showing normal morphology of all cells but a decrease in the absolute neutrophil count. Liver function test results are normal.

Which one of the following diagnoses is most likely in this case?

A. Diffuse large-B-cell lymphomA

B. Myelodysplastic syndrome

C. Felty syndrome

D. Tuberculosis

E. Portal vein thrombosis

C. Felty syndrome

About 1% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis develop Felty syndrome, with its classic triad of rheumatoid arthritis, splenomegaly, and neutropenia. Affected patients are at risk for neutropenia-related bacterial infections; if they develop frequent infections, they may require treatment with a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, such as methotrexate, which can reverse the neutropenia of Felty syndrome.

An 80-year-old man with a history of hypertension and dyslipidemia, currently taking amlodipine and atorvastatin, presents to the emergency department after a witnessed episode of loss of consciousness. He reports that he was standing up from a nap when he felt lightheaded and fell to the ground without any major trauma. He regained consciousness immediately and did not notice any change from his baseline status. On further questioning, he describes 3 months of progressive fatigue and shortness of breath on exertion, with no chest pain. He had previously been quite active and would bicycle up to 4 miles a few times per week.

On examination, he has a regular heart rate of 48 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 164/92 mm Hg, a respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and an oxygen saturation of 96% while breathing ambient air. He has no murmurs and faint bibasilar crackles. The rest of the physical examination is unremarkable.

His electrocardiogram is shown (figure).

A complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and measurement of high-sensitivity troponin, brain-type natriuretic peptide, and thyroid-stimulating hormone are all within normal limits.

An echocardiogram shows normal left- and right-ventricular function with no significant valvular disease.

The patient is currently asymptomatic at rest. His heart rate on telemetry ranges from 32 to 48 beats per minute when he is at rest and when he walks to the bathroom with assistance or ambulates with the physical therapy team.

Which one of the following management steps is most appropriate for this patient?

A. Administer 1 mg of atropine intravenously

B. Discontinue the amlodipine, and switch to losartan

C. Initiate an epinephrine infusion

D. Discharge with outpatient follow-up with primary care provider if there is no evidence of high-grade atrioventricular nodal block on 24-hour telemetry

E. Consult cardiology for placement of a permanent pacemaker

E. Consult cardiology for placement of a permanent pacemaker

The most remarkable finding on this patient’s evaluation is the sinus bradycardia, which is evident on electrocardiogram and persists on telemetry even with exertion. Bradycardia can manifest with symptoms that range from fatigue and exercise intolerance to frank syncope, with the severity of symptoms directly related to the heart rate. Patients with symptomatic sinus bradycardia should have the following potential causes ruled out: use of certain medications (beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers, antiarrhythmics, and cholinesterase inhibitors), sleep apnea, hypothyroidism, acute myocardial infarction, and electrolyte abnormalities.

If all of these causes have been ruled out (as in this case), the most likely cause of sinus bradycardia in an older adult is sinus node dysfunction, which is thought to be caused by increased collagen content and fibrosis around the sinoatrial node. The condition is typically treated with placement of a permanent pacemaker.

- A trial of atropine would be reasonable in a patient with active, moderate-to-severe symptoms of bradycardia (shortness of breath, chest pain, altered mental status, hemodynamic compromise) to improve their heart rate and reduce symptoms. However, it is not indicated in this patient, who is currently asymptomatic and hemodynamically stable while at rest in the hospital.

- Epinephrine or dopamine infusions and temporary cardiac pacing (transcutaneous or transvenous) are usually considered only in hemodynamically unstable bradycardia if atropine is ineffective and would therefore not be indicated in this case.

- Certain calcium-channel blockers can cause bradycardia, but dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers such as amlodipine do not have this effect; there is therefore no indication to switch this patient’s amlodipine to losartan.

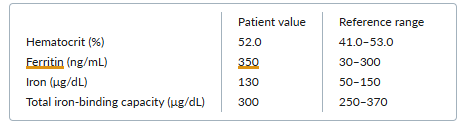

An 81-year-old man visiting the United States from El Salvador reports a 3-month history of progressive dysphagia. He has difficulty swallowing solid foods and occasionally liquids, but he has a good functional status. He has had intermittent heartburn and regurgitation for the past year but denies odynophagia. He takes hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension but denies use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, alcohol, or tobacco.

His current vital signs include a heart rate of 91 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 121/60 mm Hg. His chest and abdominal examinations are unremarkable, but his stool is black. His hematocrit is 22.9% (reference range, 41.0–53.0), down from 45.0% two years ago. Other laboratory results include a mean corpuscular volume of 70 μm3 (80–100), a platelet count of 269,000 per mm3 (150,000–350,000), a serum creatinine level of 0.8 mg/dL (0.8–1.3), and an international normalized ratio of 1.0.

The patient is admitted to the hospital, where upper endoscopy reveals extrinsic compression of the distal esophagus and a large, fungating, circumferential mass in the gastric cardia. Biopsies are obtained, and results are pending.

Which one of the following next steps is most appropriate in managing this patient?

A. Balloon dilation of the distal esophagus

B. Exploratory laparoscopy

C. Positron emission tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

D. Endoscopic ultrasound of the gastric cardia mass

E. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

E. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis

Dysphagia is a common presenting feature of a stricture in the esophagus. The most common malignant cause of stricture in the esophagus is gastroesophageal cancer. After endoscopy, which can obtain biopsies to determine tissue type and define the anatomic extent of the tumor, CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be conducted to evaluate for metastatic disease.

No other management options are indicated until the CT scan establishes whether the patient has obvious metastatic disease. Depending on the CT results, further testing could be pursued before selecting treatment. Testing options include positron emission tomography (PET), endoscopic ultrasound of the mass to assess local depth of invasion (particularly if CT reveals no metastasis) and regional nodal involvement, and exploratory laparoscopy to assess for distant metastases. Although PET imaging is sensitive for the detection of distant metastases, this case lacks tissue confirmation of malignancy. Confirmation of locoregional spread is more sensitively detected by CT imaging and is indicated in this case.

Balloon dilation is unlikely to be effective in this setting and would carry a high risk for perforation. Balloon dilation may be appropriate for palliation for carefully selected patients who have poor functional status.

A 72-year-old woman with a history of moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), stage 3 chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and chronic tophaceous gout reports several days of myalgias and weakness. Normally, she can walk around her home and perform light housework tasks, but for the past several days, she has had difficulty rising from a seated position.

Six weeks ago, she was discharged from the hospital after being admitted for a COPD exacerbation that was treated with 5 days of prednisone and antibiotics. During that admission, she had a polyarticular gout flare and was discharged home on colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily, which she continues to take along with her other long-term medications (inhaled fluticasone-salmeterol, insulin glargine, amlodipine, lisinopril, and aspirin).

On physical examination, the patient appears to be mildly tired but in no acute distress. She has a heart rate of 82 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 124/72 mm Hg, and a respiratory rate of 14 breaths per minute. Muscle strength is 4/5 in the shoulders, hip flexors, and quadriceps and 5/5 otherwise, with moderate tenderness to palpation in the lower-extremity muscles. Joint examination reveals no synovitis. Neurologic examination shows intact sensation to light touch and to temperature, with symmetric deep-tendon reflexes throughout.

Laboratory testing yields the following results:

The patient is referred for neuromuscular testing, which reveals normal nerve-conduction studies. Electromyography of the right deltoid muscle identifies fibrillation potentials and complex repetitive discharges. Biopsy of the right quadriceps identifies intracytoplasmic vacuoles without necrotic changes.

Which one of the following conditions is the most likely cause of this patient’s weakness?

A. Inclusion-body myositis

B. Colchicine-induced myopathy

C. Polymyositis

D. Glucocorticoid-induced myopathy

E. Polymyalgia rheumatica

B. Colchicine-induced myopathy

Myopathy is a rare but well-described adverse effect of colchicine therapy. The major risk factor is impaired renal function, as 20% of colchicine is renally excreted. The classic presentation is new-onset proximal muscle weakness and muscle tenderness, typically affecting the hip girdle more than the shoulder girdle, in a patient with kidney disease who recently started taking colchicine or in a patient taking long-term colchicine who develops renal impairment. In this case, the patient had stage 3 chronic kidney disease and received a prolonged course of twice-daily colchicine.

In patients with acute gout, colchicine can typically be prescribed at an initial single dose of 1.2 mg followed by a dose of 0.6 mg once or twice daily for a limited period until the flare resolves. After that, colchicine should be discontinued, unless it is being used for prophylaxis for acute gout, in which case it can be continued at a dose of 0.6 mg once daily. However, patients with renal impairment are at risk for colchicine accumulation because the drug is both filtered at the glomerulus and secreted by transporters in the proximal tubule. As a result, colchicine is often avoided in patients with renal impairment, but it may still be a reasonable treatment option if the renal impairment is taken into account during medication dosing:

• When used to treat an acute gout flare, colchicine does not need to be dose-adjusted in patients with renal impairment who are not on dialysis, whereas patients undergoing dialysis are often given a single dose of 0.6 mg of colchicine. In either case, colchicine courses should not be repeated more frequently than every 14 days.

• Colchicine for acute gout prophylaxis is best avoided, if possible, in patients with renal impairment because patients with significantly reduced renal function are at increased risk for toxicity from a prolonged course. If, after weighing the risks and benefits of other approaches for gout flare prophylaxis, a decision is made to use colchicine for this purpose, the dose should be reduced. In patients who are not undergoing dialysis but who have an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, a dose of 0.3 mg daily or 0.6 mg every 2 to 3 days is recommended. In dialysis patients, a dose of 0.3 mg twice weekly has been used.

Although this patient’s estimated GFR is slightly above the threshold at which the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends dose reduction (<30 mL/min/1.73 m2), it is important to remember that the estimated GFR is only an estimate; thus, for patients with borderline estimated GFR values, the safest choice may be to follow the recommendations for patients with renal impairment outlined above. Patients who have significant hepatic impairment and those who take medications that inhibit hepatic cytochrome P-450 3A4 or P-glycoproteins are also at risk.

In a typical case of colchicine-induced myopathy, creatine kinase levels are modestly elevated, the electromyogram shows myopathic changes, and a muscle biopsy identifies intracytoplasmic vacuoles of lysosomal origin. Symptoms usually resolve after discontinuation or dose reduction of the colchicine.

A 73-year-old man reports a 6-month history of recurrent low-grade fevers, a 3-month history of abdominal fullness, and a 6-week history of fatigue and moderately reduced exercise tolerance. He was previously in overall good health.

On examination, he appears well and in no acute distress. His heart rate is 95 beats per minute, and his blood pressure is 132/64 mm Hg. He has several palpable cervical and axillary lymph nodes (1 to 2 cm) that are nontender and freely mobile. He has a palpable spleen tip with inspiration. No hepatomegaly or abdominal masses are present. The remainder of his physical examination is normal.

Laboratory results are as follows:

The peripheral-blood smear reveals increased numbers of mature-appearing lymphocytes, increased numbers of spherocytes, and polychromasia.

Which one of the following diagnoses is the most likely cause of the anemia noted in this case?

A. Replacement of the bone marrow with chronic lymphocytic leukemia

B. Myelofibrosis with extramedullary hematopoiesis

C. Pure red-cell aplasia

D. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia

E. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

E. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) occurs more frequently in older adults than in younger individuals. Patients can present with an asymptomatic lymphocytosis found incidentally on laboratory testing. Other features that may be evident at presentation, or may develop later in the disease course, include lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and systemic symptoms such as fevers, night sweats, or weight loss.

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia occurs in 10% to 20% of patients with CLL and does not depend on disease stage. In a patient with CLL, an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level, reticulocytosis, and polychromasia (the term for reticulocytosis as seen on the peripheral smear) suggest a diagnosis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. The presence of anemia based on autoimmune hemolysis in CLL does not convey the poorer prognosis associated with anemia caused by marrow replacement.

- Two other causes of anemia in patients with CLL are pure red-cell aplasia and marrow infiltration with CLL cells. However, in such cases, the anemia is hypoproliferative and the reticulocyte count is low.

- Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, which manifests with red-cell fragments on the peripheral blood-smear, is not associated with CLL.

- Myelofibrosis can be idiopathic, or it can occur secondary to leukemias and lymphomas — but not usually CLL. Moreover, the peripheral-blood smear in myelofibrosis exhibits teardrop red cells, nucleated red cells, and early myeloid forms.

A 30-year-old man presents with fatigue that has been worsening for a year. He recently quit his construction job because of exertional intolerance. He also reports dyspnea on climbing two flights of stairs or walking more than half a mile. He has no ankle swelling, chest pain, or orthopnea. He has not seen a doctor since childhood and has no family history of cardiorespiratory conditions.

On examination, he is of normal weight and has no clubbing, cyanosis, or lower-extremity edema. A left parasternal heave is detected on precordial palpation. Cardiac auscultation reveals wide and fixed splitting of the second heart sound, with a soft systolic murmur at the upper-left sternal border. The lung fields are clear on auscultation.

A resting electrocardiogram shows an incomplete right bundle-branch block.

Which one of the following congenital cardiac abnormalities is this patient most likely to have?

A. Patent foramen ovale

B. Ventricular septal defect

C. Mitral stenosis

D. Eisenmenger syndrome

E. Atrial septal defect

E. Atrial septal defect

This patient has an atrial septal defect (ASD). Dyspnea and fatigue are common symptoms of an ASD characterized by substantial left-to-right intracardiac shunting. The splitting of the second heart sound is fixed, as phasic changes in venous return are accompanied by reciprocal changes in the interatrial shunt volume, thereby minimizing respiratory influence on pulmonary-valve closure timing. The systolic murmur results from increased forward flow across the pulmonary valve; flow across the ASD is inaudible. Electrocardiographic evidence of an incomplete right bundle-branch block is typical of ASD.

- A patent foramen ovale usually causes no cardiac symptoms or signs.

- Cyanosis or a loud P2 would be characteristic of Eisenmenger syndrome (i.e., pulmonary hypertension due to a long-standing left-to-right intracardiac shunt that results eventually in shunt reversal). Severe pulmonary hypertension is likely to cause hypertrophy of the free wall of the right ventricle and lead to a high or wide R-prime or to a pattern of marked right ventricular hypertrophy on the 12-lead electrocardiogram.

- A ventricular septal defect would cause a holosystolic murmur loudest over the lower-left sternal border.

- A mid-diastolic murmur at the apex, or a loud first heart sound would suggest mitral stenosis.

A 46-year-old man presents with a pruritic and painful rash on his hands (figure) that appeared 6 months ago and has not been alleviated by topical glucocorticoids. He has a history of chronic hepatitis C virus infection but no other significant medical history.

He is married with no children and works as a construction worker. He does not use tobacco and drinks 5 to 7 alcoholic beverages per week.

Physical examination does not reveal any stigmata of chronic liver disease. Skin examination reveals vesicles and bullae at various stages on his hands and forearms.

Laboratory testing reveals aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels that are two times the upper limit of normal. His bilirubin level and international normalized ratio are normal. Other notable results are as follows:

Which one of the following initial treatments is most appropriate for this patient’s skin problem?

A. Ribavirin and interferon

B. Abstinence from alcohol

C. Phlebotomy

D. Clotrimazole cream

E. Initiation of vitamin C

C. Phlebotomy

The blisters and erosions on this man’s hands, in combination with his history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and elevated liver-enzyme and serum ferritin levels, suggest a diagnosis of porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT).

PCT is an iron-related disorder attributable to reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, which is involved in heme synthesis.

PCT is a photosensitive condition affecting sun-exposed areas of the body. Most affected patients have multiple risk factors with HCV infection being among the most common.

The diagnosis of PCT can be confirmed via measurement of increased urine uroporphyrin and heptacarboxyporphyrin levels.

All patients with PCT who have active skin lesions should undergo primary therapy with either repeated phlebotomy or low-dose hydroxychloroquine. Phlebotomy will eventually lead to mobilization of liver porphyrins and reductions in serum ferritin levels. The primary therapy chosen depends on patient-specific factors as well as center experience; phlebotomy is more commonly used because centers have more experience with it. For patients with PCT in the setting of chronic HCV infection, direct-acting antiviral therapy can also be an effective treatment for PCT and may be used instead of phlebotomy or hydroxychloroquine.

Other important aspects of treating PCT include avoiding sun exposure, reducing modifiable risk factors (e.g., alcohol and tobacco use), and reducing iron absorption. These interventions are all secondary to initial treatment with phlebotomy.

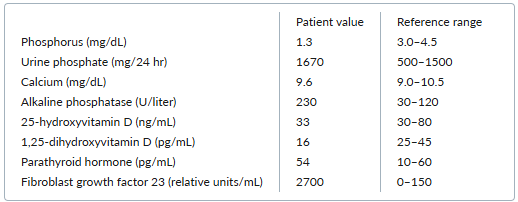

A 57-year-old woman reports experiencing progressive weakness, a 7-kg weight loss, and diffuse bone and muscle pain during the past 14 months. She used to exercise on a treadmill 5 days per week, but because of the pain and weakness, now has difficulty walking even short distances and requires a cane. Both of her parents and her two siblings are in good health.

Physical examination reveals mild kyphosis of the spine, overall weakness, and pain in both arms and legs with palpation. Radiology of the spine shows a compression fracture of T7 as well as two rib fractures. Bone-mineral density, assessed on a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan, shows T scores of –1.6 at the lumbar spine and –2.1 at the left femoral neck.

Laboratory testing yields the following results:

Which one of the following conditions is the most likely cause of this patient’s symptoms?

A. Tumor-induced osteomalacia

B. Autosomal dominant hypophosphatemic rickets

C. Fanconi syndrome

D. Secondary hyperparathyroidism

E. X-linked hypophosphatemic rickets

A. Tumor-induced osteomalacia

Tumor-induced osteomalacia is an acquired paraneoplastic syndrome caused by secretion of the hormone fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23). This hormone reduces phosphate reabsorption and vitamin D activation at the renal tubules. Consequently, elevated FGF-23 levels lead to excessive phosphate losses in the urine, thereby causing hypophosphatemia, elevated alkaline phosphatase, muscle weakness, fatigue, and osteomalacia that manifest as severe bone pain, reduced bone-mineral density, and fractures. Levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D are typically reduced, whereas levels of parathyroid hormone, calcium, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D are usually normal. The tumors that secrete FGF-23 are often small mesenchymal tumors that may be difficult to localize. Localization and resection of the tumor results in dramatic resolution of symptoms.

An 18-year-old female college student with sickle cell anemia reports having one to two painful crises a year that require hospitalization. She does not recall having ever received a red-cell transfusion. She has intermittent pain in her extremities and midback, which is relieved by nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs or acetaminophen-hydrocodone.

The patient recalls an episode of confusion, slurred speech, and left-arm and left-leg weakness that occurred in her early teens. Her symptoms resolved within minutes, and she attributed the episode to not sleeping well the previous night. A similar episode occurred again last year when she was studying for finals. Again, she attributed it to sleep deprivation.

Her only regular medication is norethindrone. She reports having occasional migraine headaches that usually occur around her menstrual periods. She does not use tobacco or illicit drugs but does drink alcohol occasionally.

Which one of the following treatments is indicated as first-line therapy for stroke prevention in this patient?

A. Red-cell exchange transfusions

B. Hydroxyurea

C. Aspirin

D. Sumatriptan

E. Iron chelation therapy

A. Red-cell exchange transfusions

Approximately 10% of patients with sickle cell disease have an ischemic stroke by age 20, and approximately 25% have one by age 45.

Chronic red-cell transfusions confer a substantial benefit in stroke prevention in patients with sickle cell disease. In this scenario, the goal of red-cell transfusions is to reduce the overall concentration of sickle hemoglobin to less than 30%. Exchange transfusion is often more effective than a simple transfusion in achieving this goal.

- Hydroxyurea has a role in the prevention of vaso-occlusive crises but is not the first-line treatment for stroke prevention. The time of onset of its action to reduce sickle hemoglobin concentration is measured in weeks to months, not hours. In a person at risk, prompt reduction of sickle hemoglobin concentration is an important goal of treatment. The TWiTCH (T ranscranial Doppler W ith T ransfusions C hanging to H ydroxyurea) trial showed that some patients may be maintained on hydroxyurea without transfusions; however, these patients had already completed at least 2 years of chronic transfusion therapy with normalization of transcranial Doppler velocities and other imaging criteria.

- Aspirin is not indicated because the mechanism of transient ischemic attacks in sickle cell disease is from sickled red cells, not platelet aggregation.

- Sumatriptan is used to manage migraine and would not be helpful in reducing the risk of stroke. Although migraine can manifest with neurologic symptoms, the clinical history usually allows it to be readily distinguished from a transient ischemic attack.

- Iron chelation therapy would be indicated in a patient who has received repeated transfusions and has evidence of iron overload.